by Felicitas Heimann-Jelinek

The Greek Stoic Zeno (336-270 BCE) postulated that all people are equal simply by virtue of being human. In practice, however, this theoretical insight played no role. For the longest time, its reflection was left to the philosophers. It was not until the American Declaration of Independence that human rights found their way into a political format. These rights, however, stopped at the indigenous population and the enslaved. On the European continent, the French Revolution made human rights a political concept. And the French Constitution of 1791 even included Jews – though by no means women. Of course, these rights did not apply to people outside the European continent.

It would take until December 10, 1948, for the “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” to be adopted by the United Nations. And it was not until September 3, 1953 that the European Convention on Human Rights was ratified.

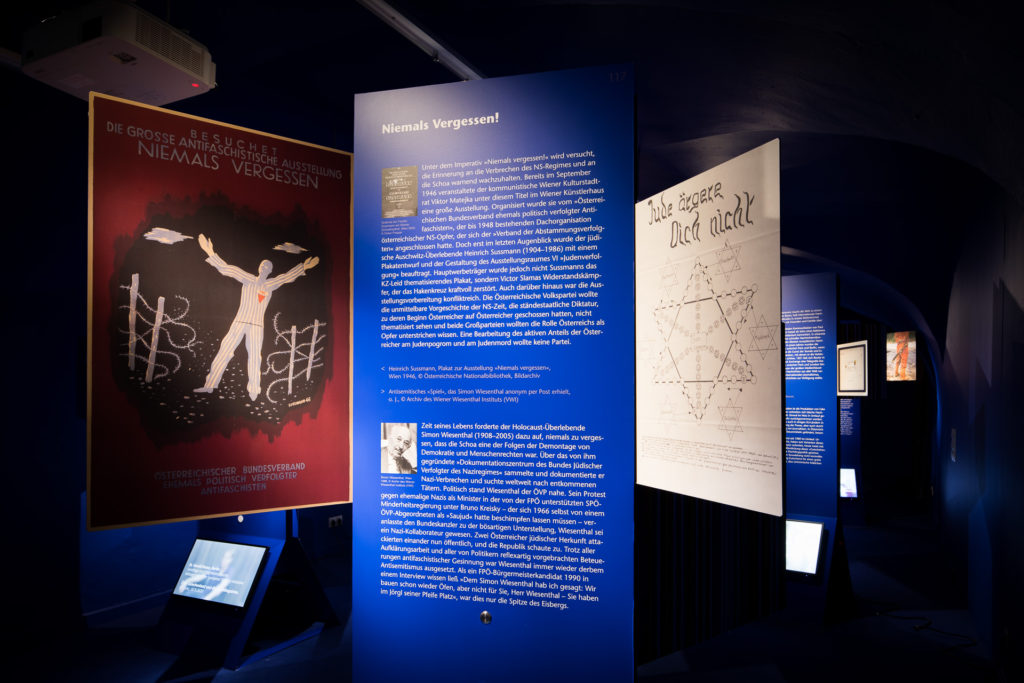

Not all of those in authority saw the necessity of a legal approach to international law, human rights, guilt and responsibility in 1945. Fritz Bauer’s work “Die Kriegsverbrecher vor Gericht” (War Criminals on Trial), published in that very year, in which he demanded “a lesson in applicable international law” for the Germans, fell on deaf ears, at least in the perpetrator societies. And yet, the drafting and passing of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights sprang from a direct reaction to the atrocities committed in connection with World War II, particularly against civilians and especially against European Jews and other minorities. Hersch Lauterpacht played a not insignificant role in the development of a universal human rights code.

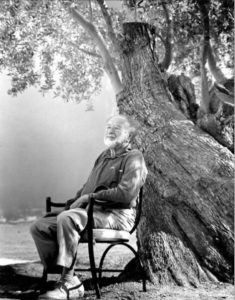

Lauterpacht, a native of what is now Ukrainian Shovkva in 1897, studied with the Constitutional Law scholar and legal philosopher Hans Kelsen in Vienna, then at the prestigious London School of Economics. From 1938 to 1955 he held the Chair of International Law at Cambridge, from 1951 to 1954 he was a member of the United Nations International Law Commission, and from 1955 until his death in 1960 he was a judge at the International Court of Justice in The Hague.

As a young man, Hersch Lauterpacht had experienced the catastrophes of the First World War. They were the trigger for his lifelong preoccupation with international law as well as human rights. The parental family of Hersch Lauterpacht had been murdered in the “Old Austrian” city of Lemberg. This may have motivated his focus on the status of the individual in international law and on the question of the proportionality of nation-state supremacy. It was in this context that Lauterpacht developed the terminology “crimes against humanity” to frame the egregious atrocities committed against civilians, a formulation that gave international law a decisive expansion. At the Nuremberg Trials, it legitimized the prosecution and conviction of Nazi actions against millions of civilian citizens. The definition was “murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation or other inhuman acts committed against any civilian population before or during war; persecution on political, racial or religious grounds, committed in the commission of or in connection with a crime over which the Court has jurisdiction, whether or not the act was contrary to the law of the country in which it was committed.” Since then, the protection of the individual against the state can also be claimed in the EU. The European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg is legally responsible for this.

At the supra-European level, the International Court of Justice in The Hague is responsible for questions and proceedings under international law. When Hersch Lauterpacht, who played a key role in drafting the European and International Conventions on Human Rights, was to be appointed as a judge by the British in 1954, voices were raised criticizing this decision with the argument that the renowned international lawyer was not “British” enough for this office, which was clearly indicated by both his origin and his name.

Hersch Lauterbach died on May 8, 1960, fifteen years after the end of WW II in London.