European Diary, 14.9.2020: The British House of Commons decides on the unilateral termination of the Brexit Treaty requested by Prime Minister Boris Johnson as part of the so-called “Single Market Act”. The fact that both British laws and international law are thereby broken seems to be of no concern not only to the Brexit Government but also to the majority of the House of Commons. The main argument is the indeed precarious status that Northern Ireland will receive in the new set of rules that Johnson whipped through parliament as a big deal not even a year ago. In a customs union with Ireland and the EU – and a customs border with the rest of the British Kingdom. At least when the negotiations for a comprehensive free trade agreement between the UK and the EU are in trouble. His predecessors John Major and Tony Blair are now “horrified”, but the exit-drunk majority doesn’t care anyway.

Once again, it is clear what price the Brexiteers are apparently willing to pay for their nationalist revolt against European unification. The laboriously achieved, yet precarious state of peace in Northern Ireland is now in danger of being deliberately sacrificed. The fact that Johnson likes to play with fire is well known. But most of his tories now follow him like lemmings. All it takes is a few absurd conspiracy theories that are becoming increasingly popular among right-wing populist leaders: the EU is planning a “food blockade” between Northern Ireland and the rest of the Kingdom.

The Brexiteers grotesquely overestimate Britain’s possibilities to play itself up as an international economic and trading power outside the EU under the protectorate of the USA. This will take its revenge when it is already too late. As it stands, in the next few years Britain will be less concerned with its great, in reality rather ailing economy than with the centrifugal forces that Brexit releases, from Northern Ireland to Scotland, and eventually in London. To which the answer is likely to be nothing more than nationalistic furor.

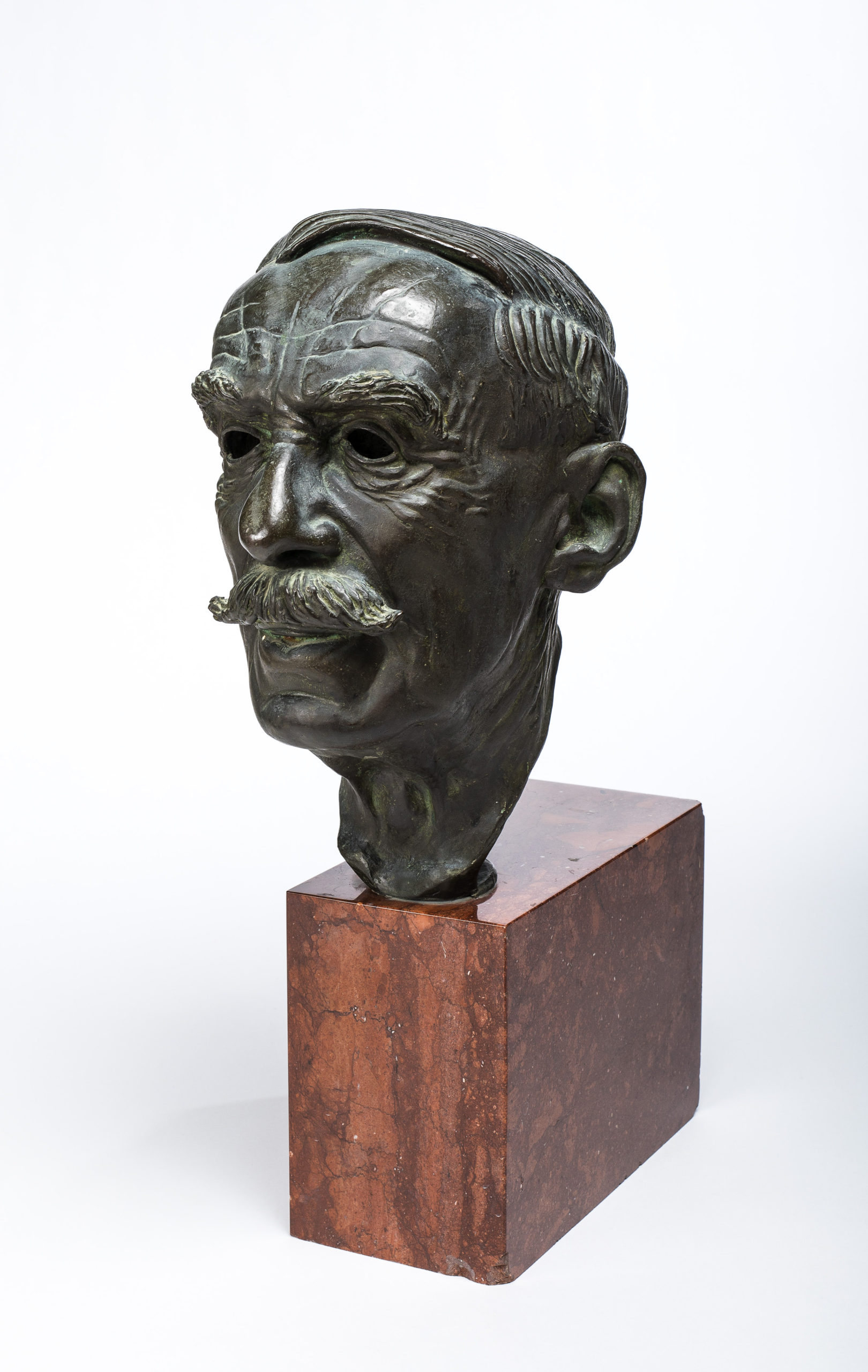

Rodolfo Brunner

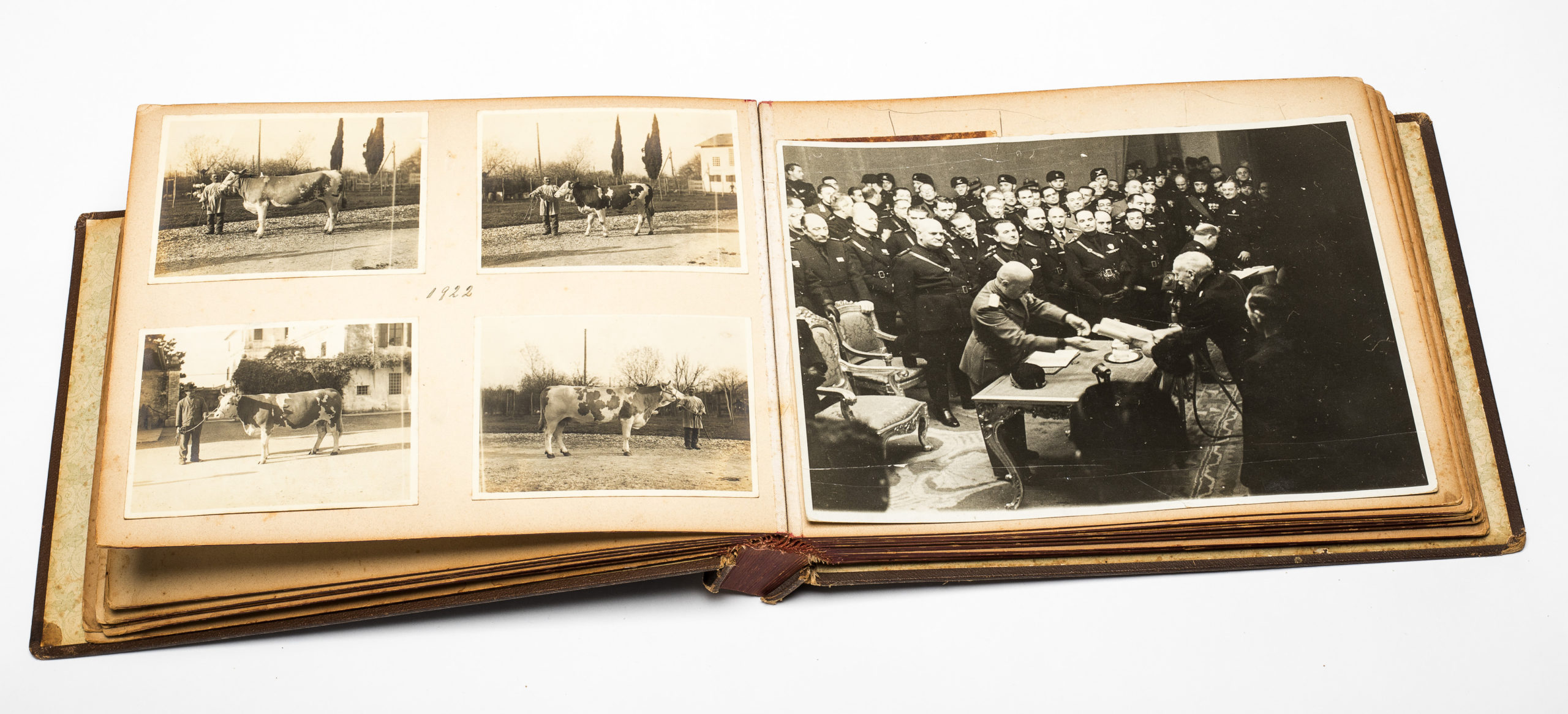

The second generation of the Hohenems immigrants in Trieste catapulted the Brunner family to their social and economic zenith. On the one hand, Rodolfo Brunner (1859-1956), eldest son of Carlo Brunner and Caroline, née Rosenthal, owned substantial shares of the family’s industrial enterprises (including chemicals, pharmaceuticals, mines, and shipping companies) and held management functions in companies such as Generali insurance, of which the Brunners were also shareholders. On the other hand, he specialized in the modernization and optimization of agriculture in Veneto and Friuli, not least in the Isonzo river delta. Politically, he was sympathetic to the Liberal-National Party of Trieste, which demanded a stronger orientation toward Italy, while he kept striving for reconciliation with Habsburg-Austrian interests. Like the majority of Trieste’s elite, but also many of the city’s Jews, he aligned himself with the Italian Fascists already early on. As business tycoon, he probably had frequent contact with the city’s top-ranking politicians. However, the reason for the meeting with Mussolini in this photograph is unknown; perhaps it is in connection with the award of the “Blue Star for Agricultural Merits,” which was bestowed on Rodolfo in 1937. His grandnephew Oscar Brunner (1900 – 1982) was an architect and sculptor, but only few of his works can be found in public collections.

Carlo Alberto Brunner

Guido Brunner

On the Austrian side, Guido was sentenced to death as renegade, but pardoned by Emperor Franz Joseph. Nevertheless, he went to war for Italy in 1915 and was killed on June 8, 1916 in the battle of Monte Fior in the Alps. His remains were never found. Guido Brunner’s horse “Trieste” survived the battle and spent the rest of its life at the Brunners’ Tuscan estate in Forcoli. In line with an equestrian tradition, a hoof was prepared after the horse’s death and used as an object of decoration or utility. The metal cap displays the inscription: “Trieste Segui in guerra il suo padrone Guido Brunner mori e fu sepolta a Forcoli li 8. XII.1918” (“Trieste — He followed his master, Guido Brunner, into war, he died, and was buried in Forcoli on December 8, 1918.”)

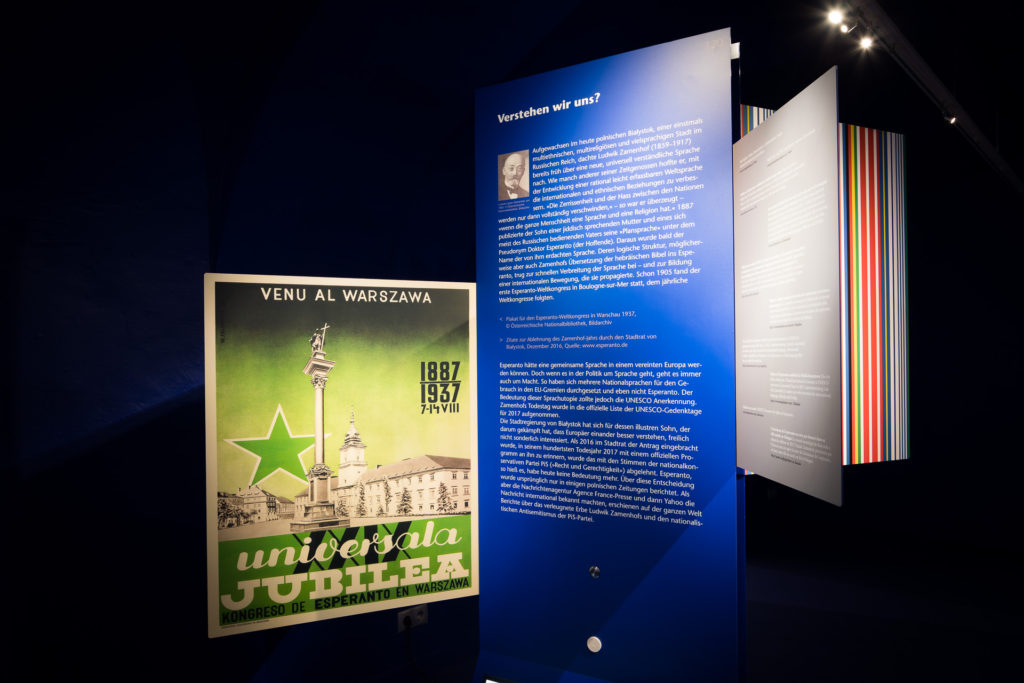

Do We Understand Each Other?

Installation Do We Understand Each Other? Photo: Dietmar Walser

Having grown up in Białystok, now Poland, a formerly multiethnic, multireligious, and polyglot city in the Russian Empire, Ludwik Zamenhof (1859–1917) began already early on to think about a new, universally understandable language. Like some of his contemporaries, he hoped to improve international and ethnic relations through the development of a easily graspable universal language. He was convinced that “division and hate among the nations will completely disappear only when all of humanity will have one language and one religion.” In 1887, the son of a Yiddish-speaking mother and a usually Russian-speaking father published his “planned language” under the pseudonym Doktoro Esperanto (the hopeful). This would soon become the name of the invented language. Its logical structure and possibly also Zamenhof’s translation of the Hebrew Bible into Esperanto contributed to the fast dissemination of the language—and to the formation of an international movement propagating it. Already in 1905, the first World Esperanto Congress took place in Boulogne-sur-Mer, which was followed by annual conventions around the world.

^ Ludwik Lejzer Zamenhof, ca. 1900, ©: Austrian National Library, Picture Archive

< Poster for the World Esperanto Congress in Warsaw 1937, © Austrian National Library, Picture Archive

> Quotes regarding the rejection of the Zamenhof-year by the Białystok municipal council, December 2016, © mounted by Günter Kassegger, source: www.esperanto.de

Esperanto had the potential of becoming a common language in a united Europe. Yet, politics and language is always also a matter of power. Hence, several national languages have prevailed for use in EU bodies and not Esperanto. However, UNESCO has paid tribute to the significance of this linguistic utopia. Zamenhof’s death anniversary was included in the official list of UNESCO commemoration days for 2017. Then again, the Białystok municipal government failed to display any particular interest in the city’s illustrious son who had worked to enable Europeans to better understand each other. When in 2016, a motion was made in the municipal council to commemorate him with an official program on the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of his passing in 2017, it was rejected with the votes of the national-conservative PiS (“Law and Justice”) party. Esperanto, it was argued, had no longer any significance today. This decision was originally reported only in several Polish newspapers. However, when this was brought to international attention by the newsagency Agence France-Presse and then by Yahoo, reports about Ludwik Zamenhof’s repudiated heritage and the PiS party’s nationalist anti-Semitism were published all over the world.

Liliana Feierstein (Berlin): About Esperanto as a Jewish, European, and International language

Gina Segré-Brunner

Gina Segrè (1867-1948) descended from a Jewish industrialist family from Trieste. Her brother, Salvatore Segrè, got involved already early on in the irredentist movement, which demanded Trieste’s disengagement from the Habsburg Empire and annexation to Italy, while the growing number of Slovenian laborers in the city championed the Pan-Slavic movement. For his aid to refugees who had fled the Austrian army in World War I, he was ennobled and made a baron, henceforth carrying the name Segrè-Sartorio. His sister, Gina, who had married Rodolfo Brunner in 1888, was also a passionate adherent of irredentism (the movement of the “unredeemed”) and was thus in political opposition to her husband. Rodolfo and Gina Brunner had four children, their older son, Guido, was killed in battle against Austria in World War I; from then on, his parents hardly spoke with each other anymore. In 1937, Gina Brunner was appointed president of the national association of mothers and widows of war victims. The tableware features the Segrès’ old family coat of arms “Omnia pro patria libenter.”

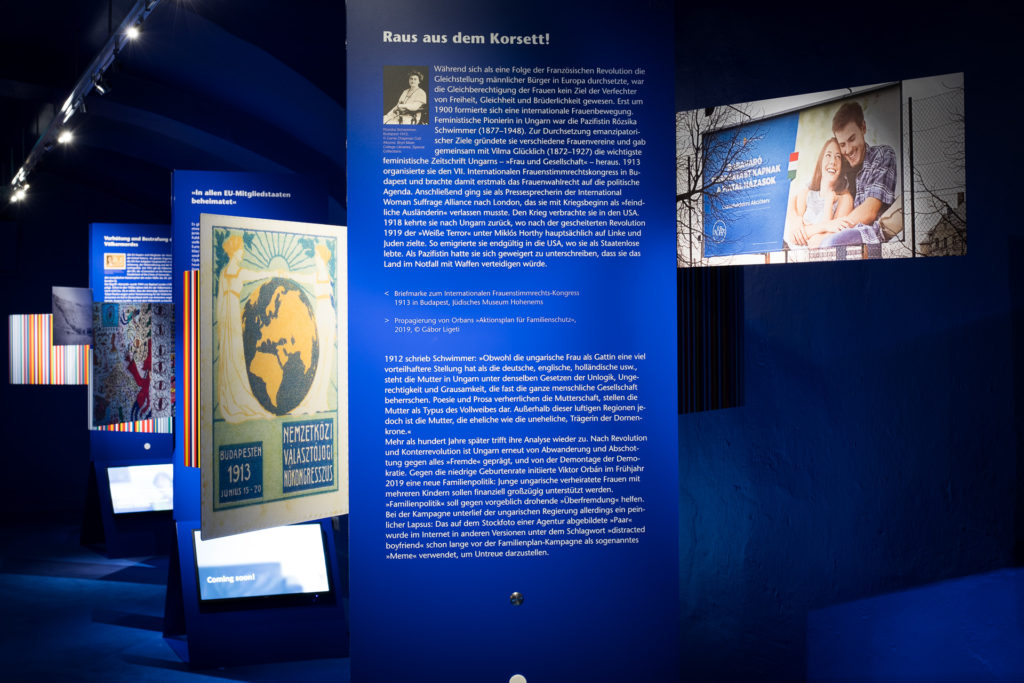

Escape the Corset!

Installation Escape the Corset!. Photo: Dietmar Walser

While in the wake of the French Revolution, equality for male citizens was met in Europe with acceptance, the emancipation of women had not been among the goals of those championing liberty, equality, and fraternity. Only around 1900, an international feminist movement began to emerge.

< Stamp on the occasion of the 1913 Conference of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance in Budapest, © Jewish Museum Hohenems > Promotion of Orbán’s “family protection action plan,” 2019, © Gábor Ligeti

In 1912, Schwimmer wrote: “Although as wife, the Hungarian woman is in a much more advantageous position than the German, English, Dutch, etc., the mother in Hungary is subjected to the same laws of illogic, injustice, and cruelty that govern almost all of human society. Poetry and prose exalt motherhood, depict her as a type of earth mother. Yet, outside of these lofty regions, the mother, married or unmarried, is the carrier of the crown of thorns.” More than one hundred years later, her analysis is once again applicable. Following revolution and counterrevolution, Hungary is once more characterized by emigration and sealing-off against anything “alien” as well as by the dismantlement of democracy. In the spring of 2019, Viktor Orbán initiated a new family policy to combat the low birthrate: young Hungarian married women with several children would receive generous financial support. “Family policy” is intended to ward off the supposedly impending Überfremdung (excessive influx of foreigners). However, in the course of the campaign, the government had committed an embarrassing blunder: already long before this family-planning campaign, the “couple” depicted on an agency’s stock photograph had been circulating the internet in other versions under the slogan “distracted boyfriend” as a so-called “meme” to illustrate infidelity.

Andrea Petö (Vienna) about women’s rights, gender studies and Corona:

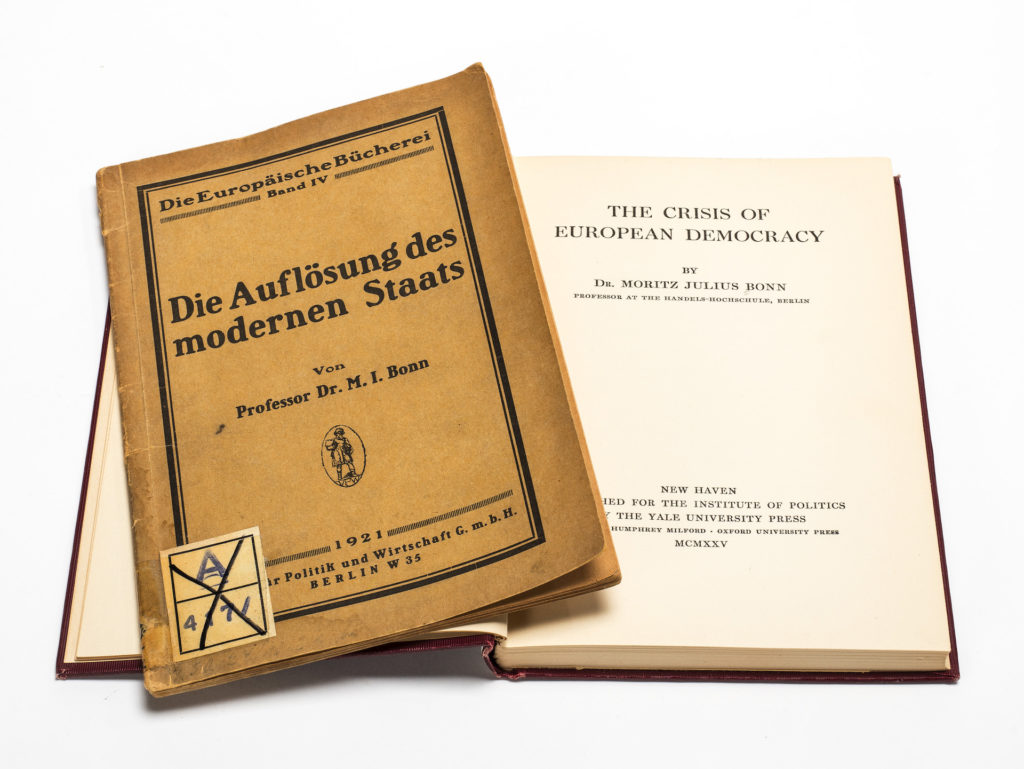

Moritz Julius Bonn

Moritz Julius Bonn was born on June 16, 1873 in Frankfurt am Main as son of the banker Julius Philipp Bonn and Elise Brunner of Hohenems. Following studies in Heidelberg, Munich, Vienna, Freiburg, and London as well as research visits in Ireland and South Africa, he started his successful career as a political economist. In Italy, he met Theresa Cubitt, a native of England and married her in London in 1905. That same year, he completed his habilitation on English colonial rule in Ireland. From 1914 to 1917, he taught at various universities in the USA. As a political consultant, he took part in numerous postwar conferences, wrote on the topics of free trade and economic reconstruction, and drafted critical studies on colonialism as well as European democracy, which he considered viable only if based on pluralism and ethnic diversity. As rector of the Berlin College of Commerce and head of the Institute of Finance, founded by him, he eventually became one of the leading economic experts of the Weimar Republic. In the wake of the National Socialist seizure of power in 1933, Bonn was forced to emigrate, initially to Salzburg, then London, and finally to the USA where he began his autobiography Wandering Scholar (German: So macht man Geschichte). After the war, he permanently settled in London where he passed away in 1965. Moritz Julius Bonn had spent his childhood summers at his grandparents’ in Hohenems and also