European Diary, 3.8.2021: 73 years ago today, Rosika Schwimmer died in New York

by Felicitas Heimann-Jelinek

Today, the term “feminism” can no longer be explained in one sentence, let alone translated with a single term. Feminism today means a complex pool of currents of socio-political concerns and agendas. Thus, the current discourse speaks of feminisms, not feminism – and the respective interpretations and functions of contemporary feminisms are shaped by questions about the respective socially conditioned specific dimensions of natural or constructed, social and ethnic gender.

Rosika Schwimmer, born into a Jewish family in Budapest on September 11, 1877, could hardly have imagined such a differentiation, even as one of the most prominent women’s rights activists of her time. But she was a surprisingly modern feminist. She was not only concerned with women’s rights, but with the rights of all. She vehemently opposed child labor and fought for world peace.

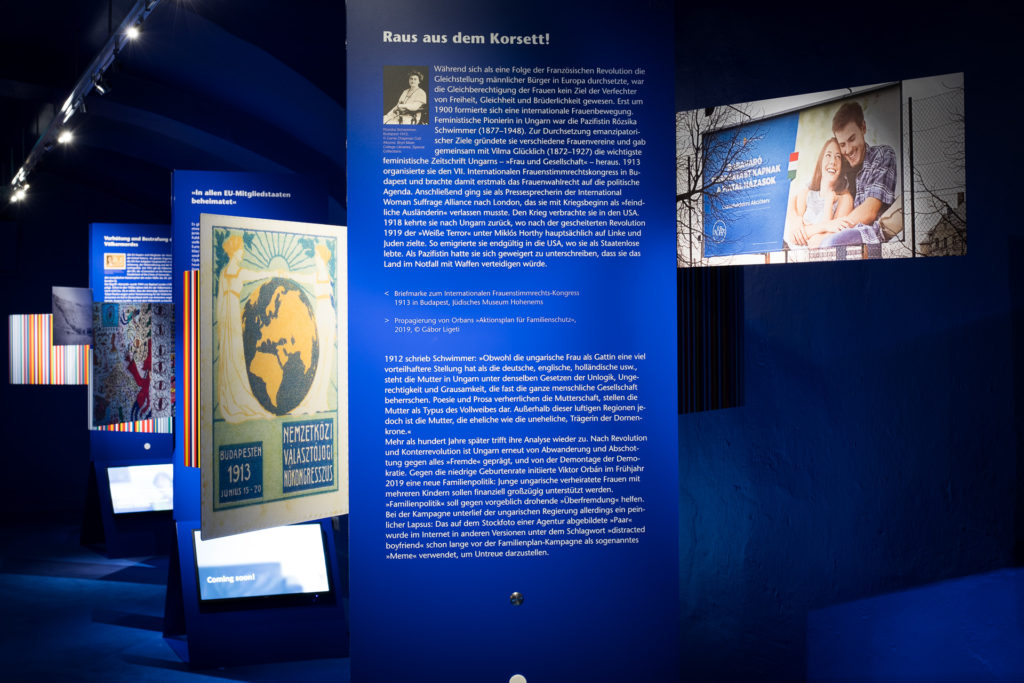

Rosika Schwimmer did not conform to the norm of a woman of her time. After a year of marriage, she divorced. Most likely she was lesbian, but disciplined her sexuality with morphine. She was stubborn, opinionated, dominant, dynamic – a fighter. In 1897 she founded the Association of Female Office Workers, in 1903 the first Hungarian Women Workers’ Association, and finally in 1904 the Association of Hungarian Feminists. Rosika Schwimmer also did not conform to the female ideal of beauty, nor did she follow the dress code of her time. She tended to be corpulent, wore a bun, pince-nez and – no corset. By the standards of the time, she did not act in a “typically feminine” way, but rather in a “typically masculine” way. As a campaigner for economic, social and political equality, she earned a reputation as a leading advocate of women’s rights in Hungary.

When Schwimmer first arrived in the United States in 1914, she was welcomed with open arms. The Jewish press gushed with euphoria over “Hungary’s great Jewess, darling of women’s rights activists in Europe and America.” Fifteen years later, the right-wing press overflowed with hatred against her. Sometimes she was accused of being a spy for the Germans, sometimes of being one for the Bolsheviks, but above all, “far more dangerous,” of being an “agent of the political-economic movement of Jewry.” By this time, she no longer had any support in the American Jewish community.

For Rosika Schwimmer’s “Peace Ship Expedition” in 1915 had made her even better known internationally as a pacifist than she already was as a feminist. Together with Louis Lochner, she persuaded automobile tycoon Henry Ford to send an amateur diplomatic mission to Europe to broker an end to the First World War. But the mission, widely derided by the press, was unsurprisingly unsuccessful. In this context, American Jews distanced themselves from Schwimmer, accusing her of fomenting Henry Ford’s anti-Semitic campaign during the short-lived, yet highly publicized Peace Ship Expedition. The campaign was no slip; Ford repeatedly engaged in anti-Semitic publicity. During the Nuremberg trial, the Reichsjugendführer of the NSDAP, the Viennese Gauleiter and Reichsstatthalter Baldur von Schirach was to declare: “The decisive anti-Semitic book that I read at that time and the book that influenced my comrades […] was the book by Henry Ford The International Jew. I read it and became an anti-Semite.” No wonder, then, that many co-religionists considered her a traitor. In 1919, Schwimmer briefly became Hungarian ambassador to Switzerland, but soon after she had to flee Budapest to Vienna to escape the White Terror and emigrated to the United States, where the consistent pacifist was denied naturalization.

From today’s perspective, Rosika Schwimmer operated on the left fringe of the pacifist and feminist movements. In the service of the good cause she was not very squeamish and instrumentalized whom she could instrumentalize. Her uncompromising attitude made her a challenged outsider in a war-driven world of isms and anti-isms where racism, chauvinism, anti-communism, anti-feminism, and anti-Semitism were commonplace.

But she experienced satisfaction: shortly before Schwimmer died stateless in New York in 1948, she had been chosen as a candidate for the Nobel Peace Prize. She could not have known that, basically only 20 years later, her feminist activism would be taken up again in the West and that the new women’s movement would stand up stronger than ever to the asymmetrical gender relations in family, society, politics and religion.