European Diary, 22.1.2021: 110 years ago today, Bruno Kreisky was born in Vienna. To this day, the memory of the probably most popular chancellor of the republic is polarizing., a chancellor who was at the same time anything but a typical Austrian politician. His political opponents in particular left no doubt about this. In 1970, ÖVP Chancellor Josef Klaus ran for office with the slogan “A real Austrian. This, according to the party’s calculations, said everything there was to say about Kreisky, a Jew and emigrant. But Bruno Kreisky led the SPÖ to a relative majority of 48.5 %. And after an interlude of a cabinet tolerated by the FPÖ, which was highly controversial even among his friends, the SPÖ achieved an absolute majority three times in a row with Kreisky. It’s been a long time, one might say.

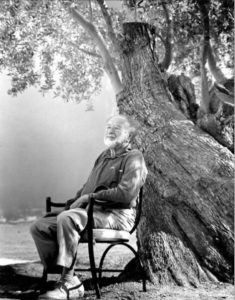

Bruno Kreisky

Photo: Konrad Rufus Müller / Source: Kreisky Forum for International Dialogue

Kreisky had no qualms about working with former National Socialists. Precisely because he did not want to be told that he was doing politics as a Jew. Kreisky was above all a European politician, and his own experience of persecution and exile had taught him his own Austrian patriotism: which consisted of not wanting to be a nationalist. And certainly not a Jewish nationalist.

This was eventually to drive him into a dispute in which neither his opponent nor he himself could reap any glory. His bitter feud with the arch-conservative Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal stands to this day like an erratic block in the Austrian memory landscape.

Simon Wiesenthal, whose good relations with the Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) were not a bit clouded by the traditional anti-Semitism of the Christian Socialists, gleefully scandalized Kreisky’s lack of inhibitions about cooperating with former Nazis, whether such in the FPÖ or those in the SPÖ. Four of the thirteen ministers in Kreisky’s Social Democratic cabinet in 1970 had belonged to the NSDAP. And FPÖ leader Friedrich Peter, with whom Kreisky was considering a coalition in 1975, had been active in an SS terror unit, which Wiesenthal also deliberately brought to public attention.

Kreisky’s subsequent insults against Wiesenthal (“Nazi collaborator”) are legendary. Austria was able to watch two Jews at each other’s throats in public. But behind the dispute was by no means only Kreisky’s political calculation to curry favor with parts of the electorate. Behind it was – more or less unspoken – the dispute about Jewish experiences from which Wiesenthal and Kreisky had drawn diametrically opposed conclusions.

Kreisky’s traumatic experiences did not begin in 1938 with National Socialism, but in the Austrian fascism of the Ständestaat. In 1936, the young socialist Kreisky was sentenced to imprisonment. He had every reason to distrust the political descendants of the Austrofascists as much as the National Socialists, who drove him into exile in 1938. Kreisky survived in Sweden, where he also met Willy Brandt, who had emigrated from Germany – the beginning of a lifelong friendship.

Kreisky remained a passionate European, but he did not like Zionism. For him, there was no question of helping to build a democratic Austria after 1945. His four chancellorships were marked by reform initiatives in social policy and education policy, as well as in family and criminal law – and, as with so many Social Democrats, by a confidence in technical progress that also made him blind to the new issues that came onto the agenda with the dispute over the Zwentendorf nuclear power plant. Even defeat in the referendum, however, did not prevent him from winning the 1979 elections for the fourth time.

While Wiesenthal made Israel as a “Jewish state” the core of his own identity in Austria, Kreisky tried to mediate in the Middle East conflict. Which entangled him in contradictions. He cultivated relations with Arab politicians such as Sadat and Gaddafi, and discreetly negotiated with Moscow for the release of Jewish Soviet citizens who wanted to emigrate to Israel.

What Kreisky mastered best was the art of playing with the public. His press conferences are unforgotten. Not necessarily what they were about in each case. But the style was new. Instead of pronouncements, there was communication.

“I don’t value wreaths that posterity will weave for me. I don’t value monuments. What I would like, however, is for the period in which I was able to influence political conditions in Austria to be regarded as a period in which great reforms were introduced, which left their mark on society and brought about an improvement in social conditions. Nothing would be more gruesome than the thought of having merely administered.”

Much of what Kreisky wanted to set in motion is still waiting to happen.

Willy Brandt, Kreisky’s companion for over fifty years, delivered the eulogy for him at Vienna’s Central Cemetery. “Farewell, my dear, my difficult friend.”