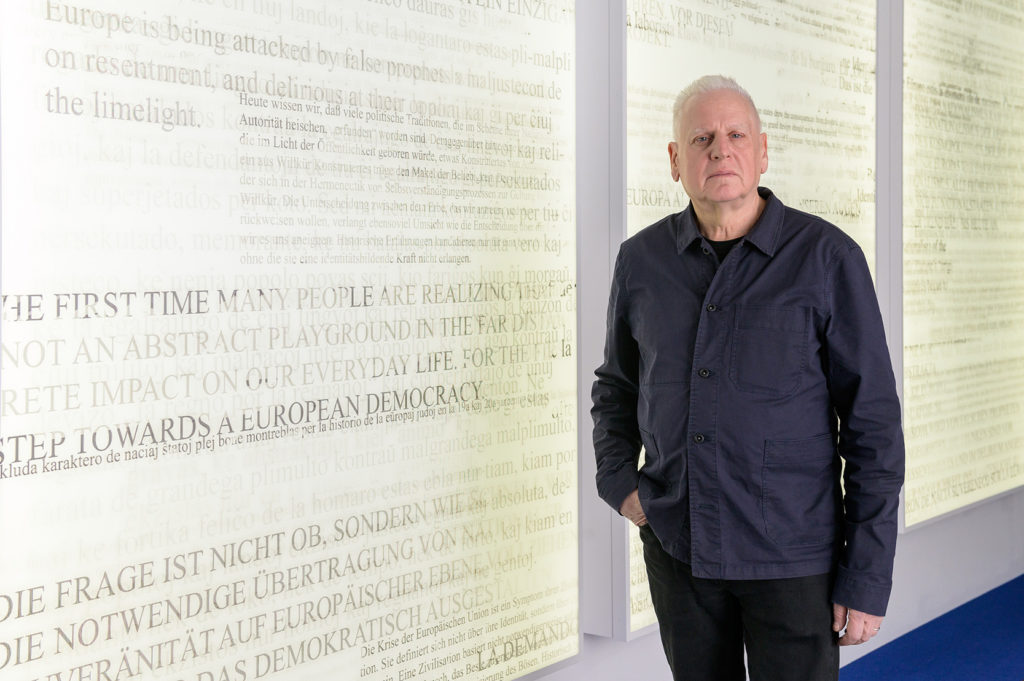

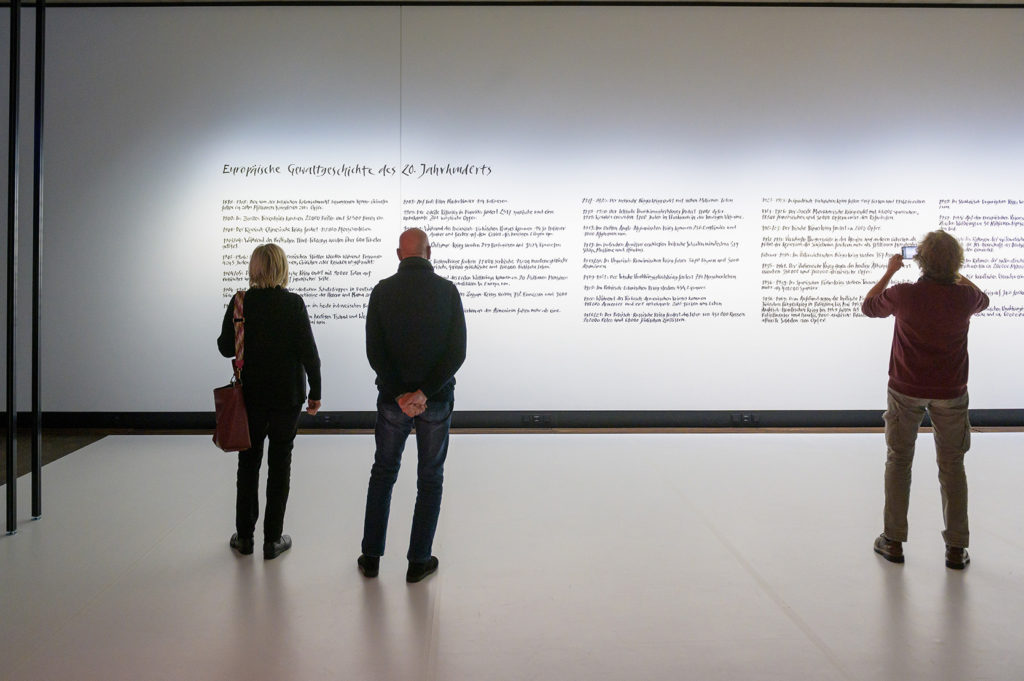

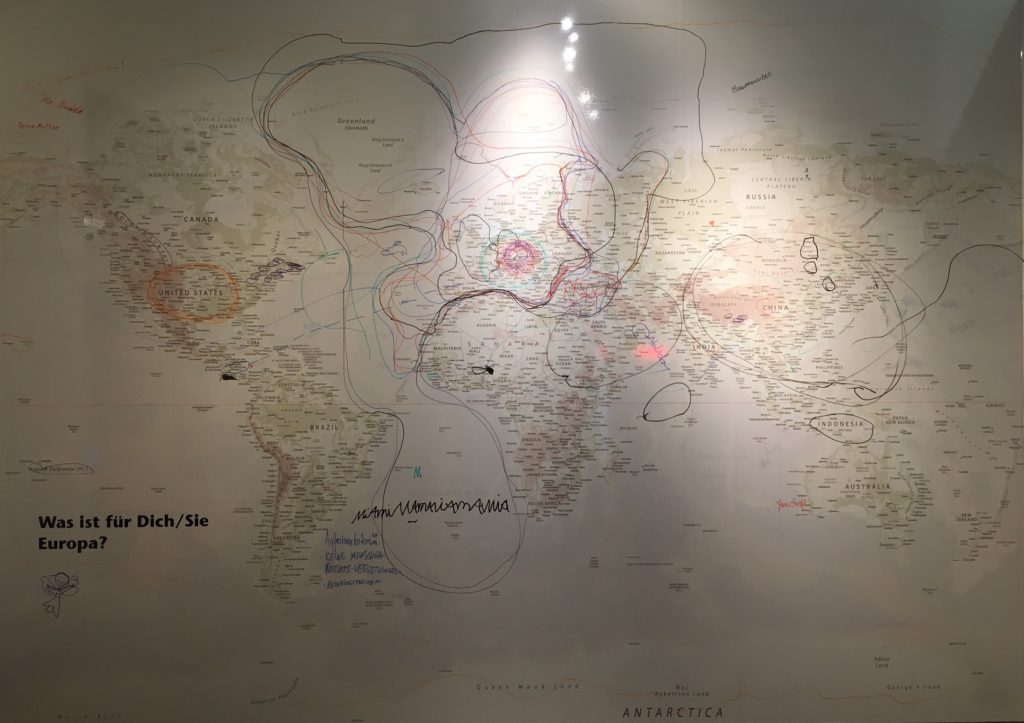

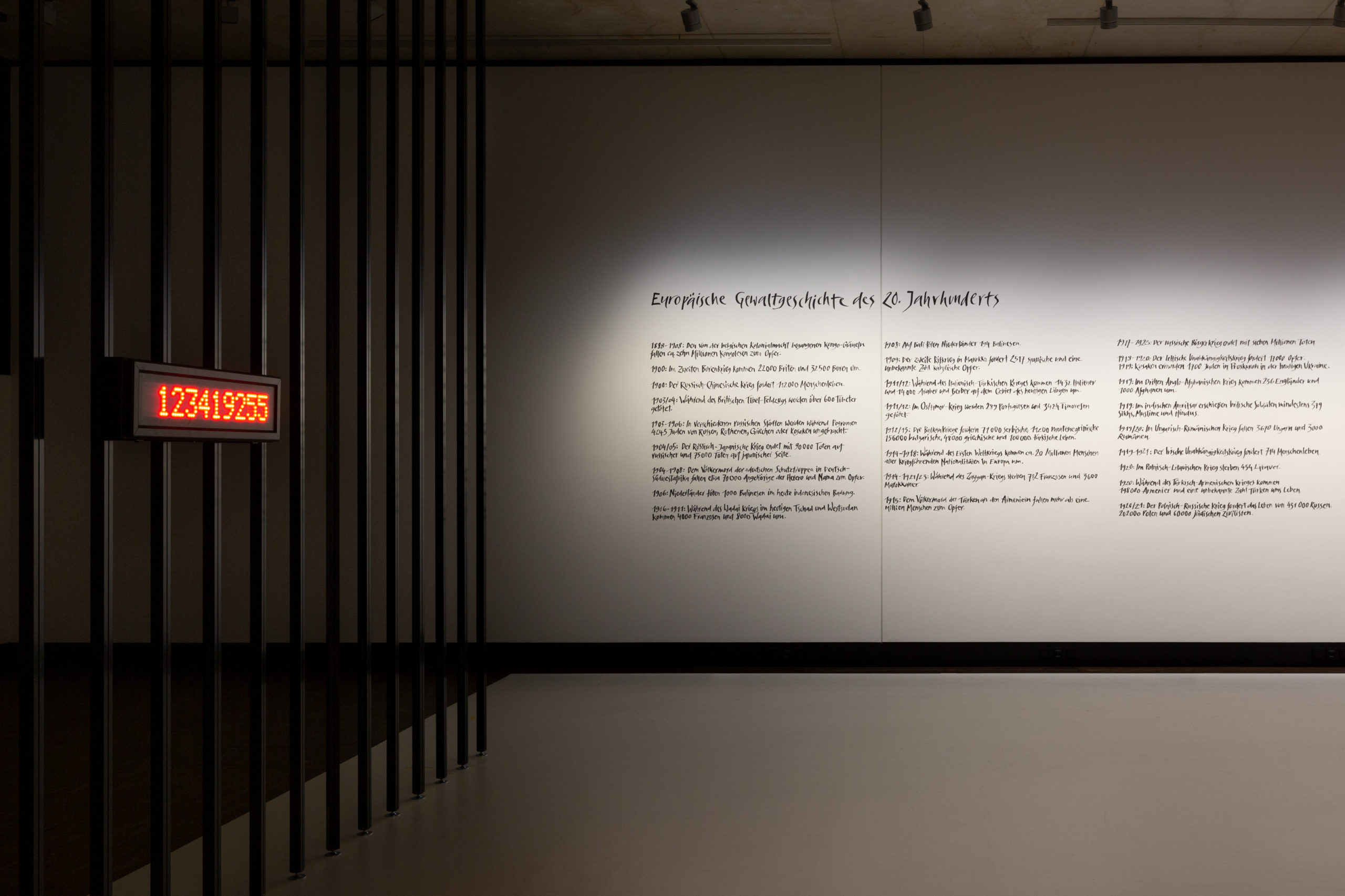

Photo: Daniel Schvarcz

Our list of the dead of European violence in the 20th century counts 125,300,000 people. It is not complete.

By the end of the exhibition “The Last Europeans” on May 21, 2023, they will have disappeared from the display.

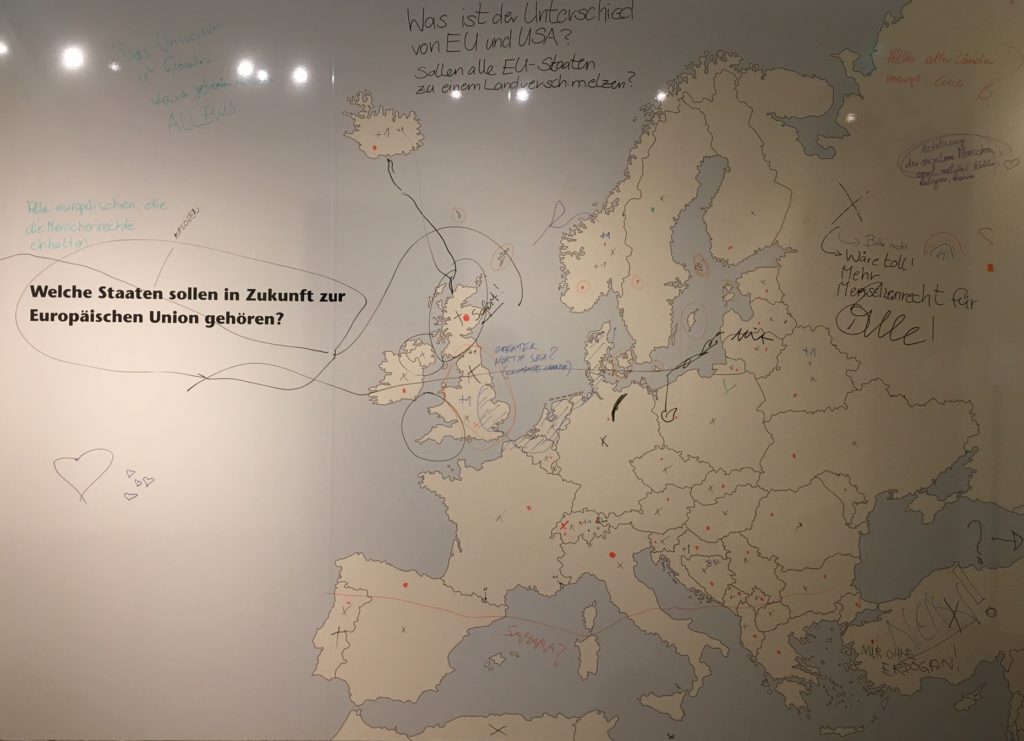

Foto: Eva Jünger

1888–1908: The atrocities committed by the Belgian colonial power in Congo claim approx. ten million Congolese victims.

1900: In the course of the Second Boer War, 22,000 Britons and 32,500 Boers perish.

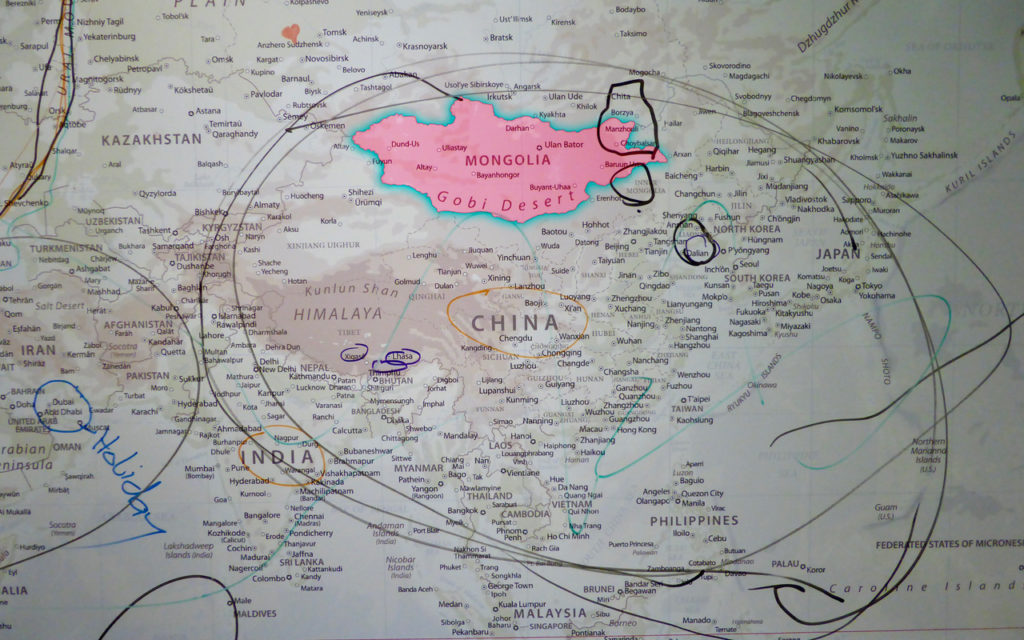

1900: The Russian invasion of Manchuria claims 112,000 lives.

1903/04: During the British expedition to Tibet, more than 600 Tibetans are killed.

1903–1906: In various Russian cities, 4,245 Jews are murdered during pogroms carried out by Russians, Ruthenians, Greeks, or Cossacks.

1904/05: The Russo-Japanese War ends with 90,000 casualties on the Russian and 75,000 on the Japanese side.

1904–1908: In German South West Africa, approx. 70,000 members of the Herero and Nama fall victim to the genocide at the hands of the “German Schutztruppe” (protection force).

1906: Dutchmen kill 1,000 Balinese in today’s Indonesian Badung.

1906–1911: The Wadai War in today’s Chad and western Sudan claims 4,000 French and 8,000 Wadai victims.

1908: In Bali, Netherlanders kill 194 Balinese.

1909: The second Melilla war in Morocco claims 2,517 Spanish and an unknown number of Kabyle victims.

1911/12: In the course of the Italo-Turkish War, 1,432 Italians and 14,000 Arabs and Berbers meet their death in the territory of today’s Libya.

1911/12: In the East Timor war, 289 Portuguese and 3,424 Timorese are killed.

1912/13: The Balkan Wars claim 71,000 Serbian, 11,200 Montenegrin, 156,000 Bulgarian, 48,000 Greek, and 100,000 Turkish lives.

1914–1918: In the course of World War I, about 20 million people of all belligerent nationalities perish in Europe.

1914–1921/23: During the Zaian War, 782 French and 3,600 Moroccans die.

1915: More than one million people fall victim to the Turks’ genocide of the Armenians.

1917–1923: The Russian civil war results in seven million dead.

1918–1920: The Latvian independence war claims 17,000 victims.

1919: Cossacks murder 1,700 Jews in Proskurov in today’s Ukraine.

1919: The Third Anglo-Afghan War claims 236 British and 1,000 Afghan lives.

1919: In Amritsar, India, British soldiers shoot and kill at least 379 Sikhs, Muslims, and Hindus.

1919/20: In the Hungarian-Romanian War, 3,670 Hungarians und 3,000 Romanians lose their lives.

1919–1921: The Irish War of Independence claims 714 lives.

1920: In the Polish-Lithuanian War, 454 Lithuanians die.

1920: In the course of the Turkish-Armenian War, 198,000 Armenians and an unknown number of Turks perish.

1920/21: The Polish-Soviet War claims the lives of 431,000 Russians, 202,000 Poles, and 60,000 Jewish civilians.

1921–23: During the Greco-Turkish War, 9,167 Turks and 19,362 Greeks lose their lives.

1921–1926: The Rif War ends with 63,000 Spanish, 18,500 French, and 30,000 Riffian victims.

1922/23: The Irish Civil War claims around 2,000 victims.

1932-33: Famines in Ukraine and other areas of the Soviet Union, exacerbated as a means of repression, claim more than 3,000,000 lives.

February 1934: In the Austrian Civil War, 357 people die.

1935–1941: The Italian war against today’s Ethiopia claims between 350,000 and 760,000 Abyssinian victims.

1936–1939: During the Spanish Civil War, thousands of interbrigadistas and more than 400,000 Spaniards die.

1936–49: The revolt against the British mandatory power, the Arab-Jewish civil war in Palestine until May 1948, and the subsequent Arab-Israeli war until 1949 claim the lives of 165 Britons, 6,000 Jewish Palestinians and Israelis, 9,000 Arab Palestinians, and 5,000 Arab allied soldiers.

1939: In the Slovak-Hungarian War, 22 Slovaks and eight Hungarians perish.

1939–1945: In the course of World War II, approx. 50 million people of all belligerent nations meet their death in the European theaters of war.

1939–1945: In the context of the systematic annihilation of the European Jews by the German Reich’s National Socialist regime, approx. six million Jews are murdered.

1939–1945: In the context of the systematic annihilation of the Roma by the German Reich, approx. 200,000 members of these groups are murdered.

1941–1945: The Croatian Ustasha murder 500,000 Jews, Serbs, and Roma. 1945: The Battle of Surabaya, East Java, claims 1,000 British and 12,000 Indonesian lives.

1945–1949: In the Indonesian War of Independence, 1,200 British, 6,125 Dutch, and approx. 60,000 Indonesian soldiers perish.

1945–1950: In the context of the expulsions from Central- and Eastern Europe, more than 500,000 Germans perish.

1946: Inhabitants of the Polish city of Kielce kill forty Jews.

1946–1949: In the Greek Civil War, 50,000 people die a violent death.

1946–1954: In the course of the First Indochina War, 130 000 French and one million Vietnamese, Cambodians, and Laotians lose their lives.

1948–1960: During the Malayan Emergency, Britons kill more than 10,000 Malaysians.

1952–1956: In the course of the Tunisian independence war, 17,459 French soldiers and at least 300,000 Tunisians perish.

1952–1960: During the Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya, 200 British soldiers and 20,000 guerilla fighters perish.

1954–1962: In the Algerian War of Independence, approx. 24,000 French soldiers and approx. 300,000 Algerians lose their lives.

1961: The French police carry out a massacre against 200 Algerians in Paris.

1963–1964: The Cypriot civil war claims 174 Greek and 364 Turkish lives.

1968–1998: In the Northern Ireland conflict, 3,500 people perish.

1974: The Turkish invasion of Cyprus claims the lives of 3,000 Turks as well as of 5,000 Greek and Turkish Cypriots.

1979–1989: In the course of the Soviet-Afghan War, 14,453 Soviet soldiers and approx. one million Afghans lose their lives.

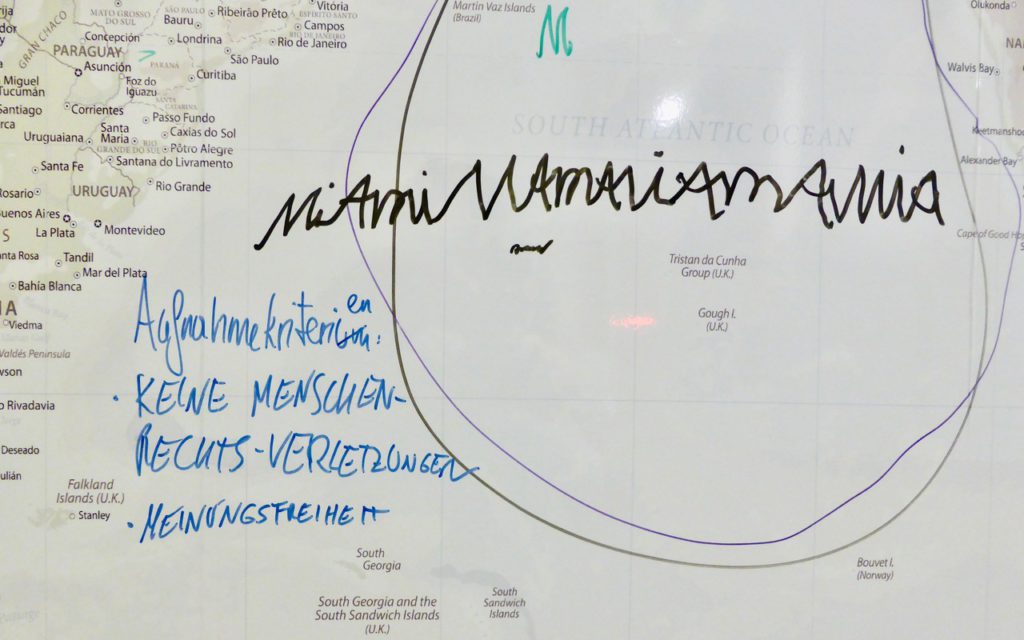

1982: In the Falklands War, 258 British and 649 Argentinian soldiers die.

1991–1995: The Yugoslav Wars claim 52,800 Bosnian, 18 530 Croatian, 30,000 Serbian, 4,000 Kosovar, and 800 Albanian lives.

1995: In Srebrenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbs carry out a massacre against 8,000 Muslim Bosniaks.

1992–93: In the Georgian Civil War, 10,000 people perish.

1998/99: The Kosovo War claims the lives of 2,170 Serbs and 10,527 Albanians.

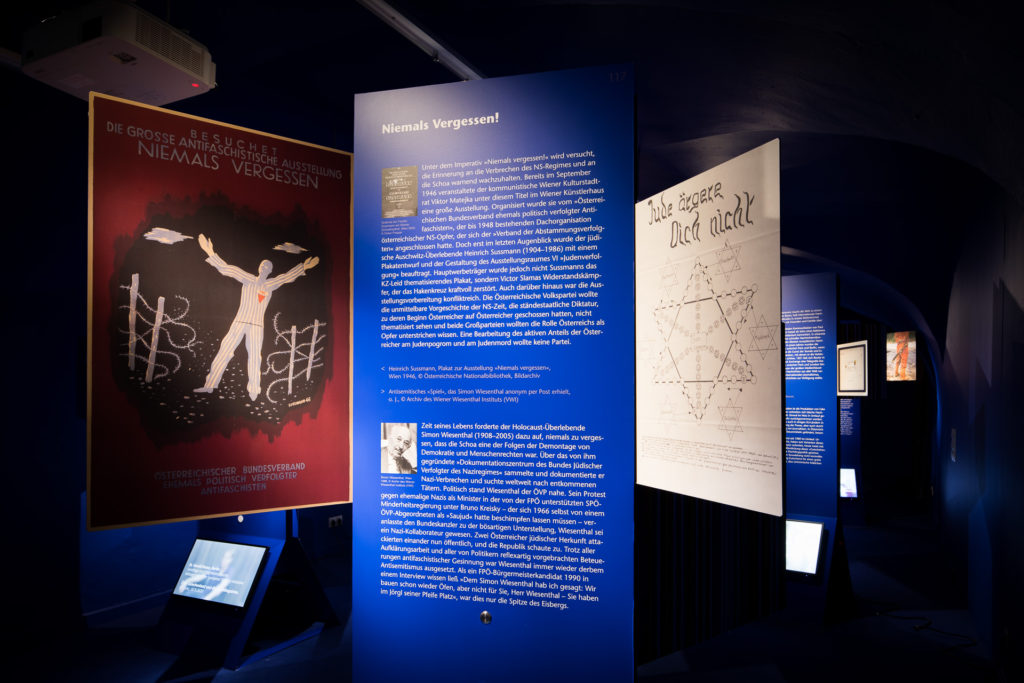

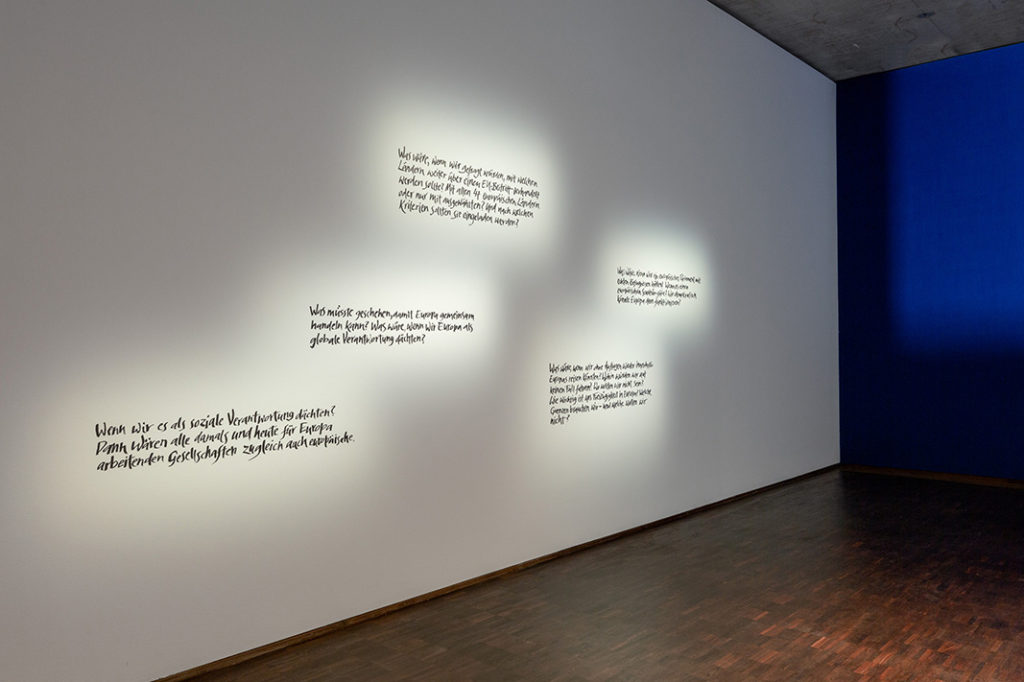

Photo: Daniel Schvarcz

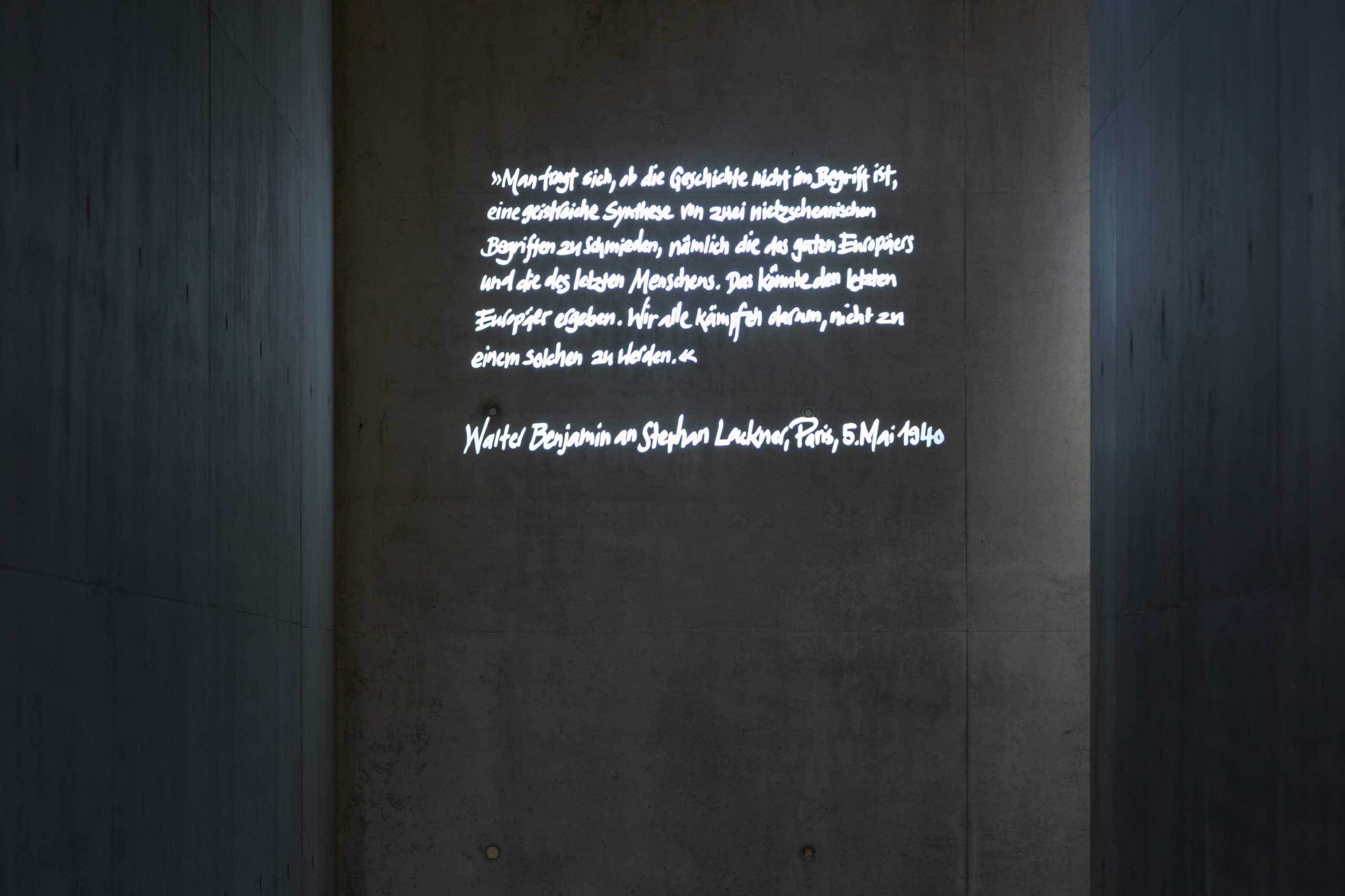

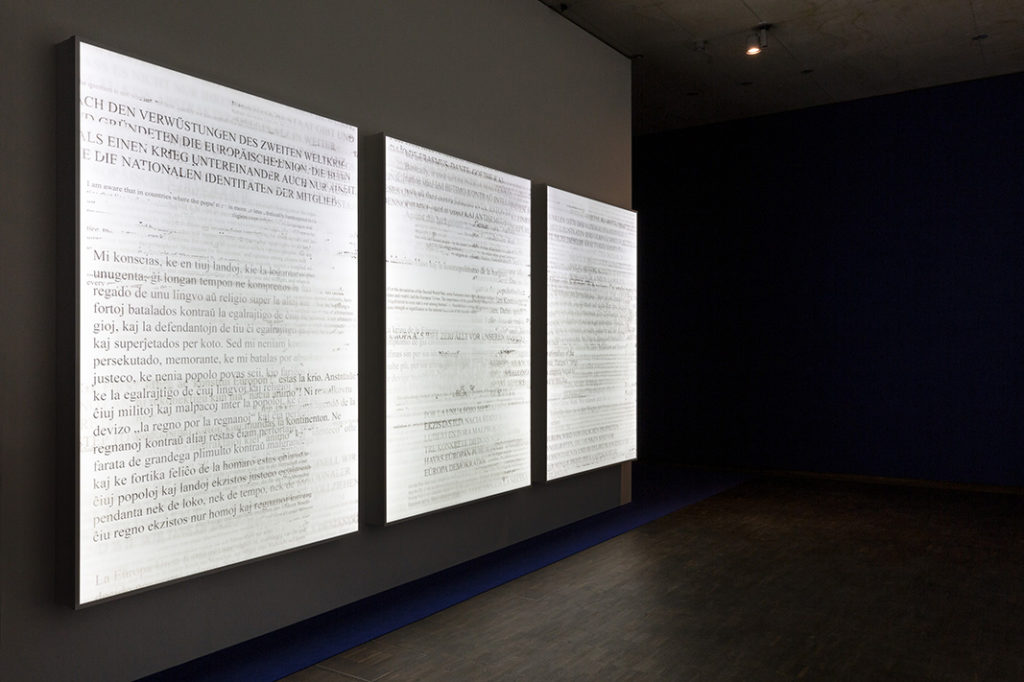

Photo: Daniel Schvarcz

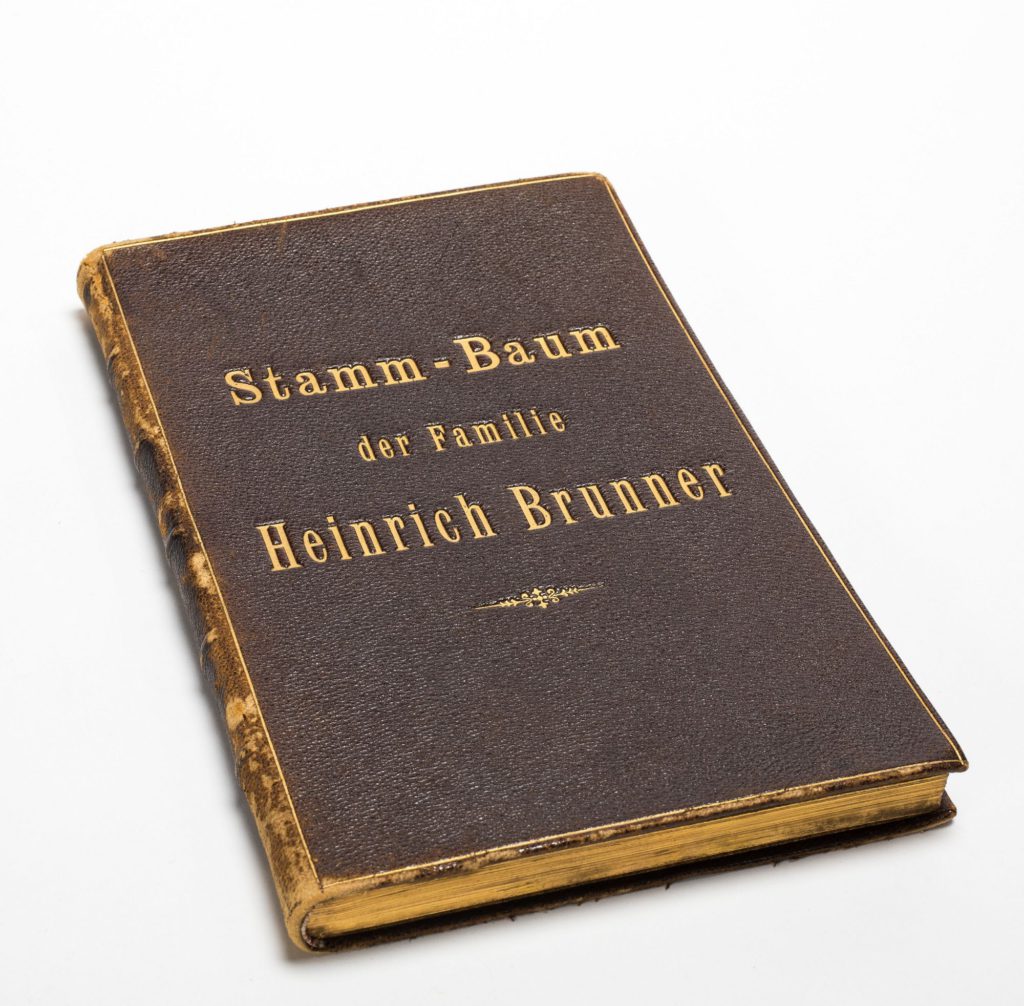

Portrait of Helene Brunner, about 1830, Jewish Museum Hohenems, Carlo Alberto Brunner Estate

Portrait of Helene Brunner, about 1830, Jewish Museum Hohenems, Carlo Alberto Brunner Estate