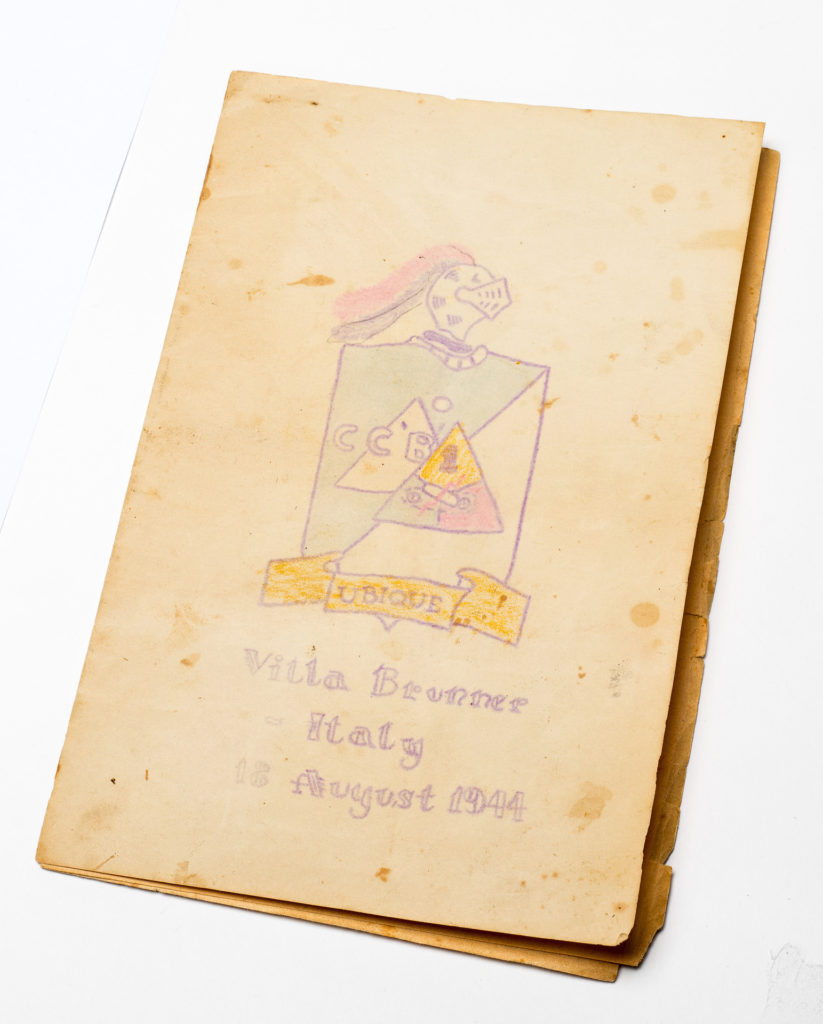

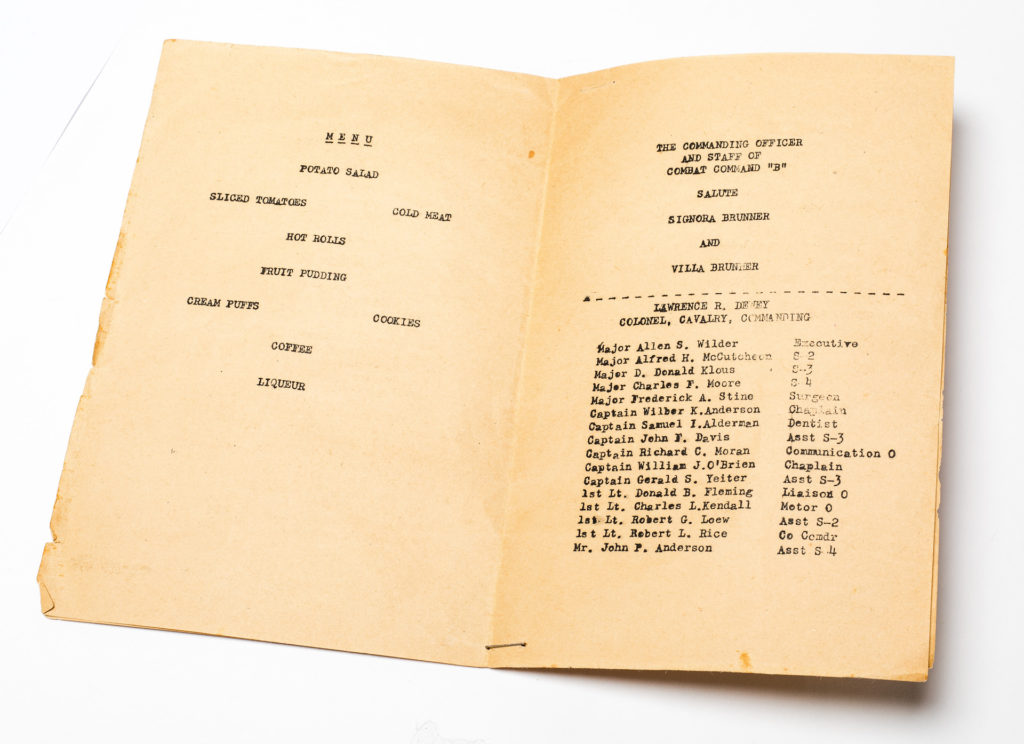

In 1916, Rodolfo Brunner had acquired the large compound of Forcoli in Pontedera, Tuscany, which almost three decades later would become a refuge for some family members while other members of the Brunner family escaped to Switzerland or left for England in time. After the invasion of the German Wehrmacht in September 1943, Rodolfo and his wife, Gina, his daughter-in-law Maria Teresa (“Tea”) Brunner, née Clerici (1908-1947), and her four children fled to Forcoli; here they did not raise the German invaders’ suspicions and survived war and persecution while Leone Brunner, Tea’s husband, was involved in the resistance against the National Socialists. In honor of the American liberators, Tea Brunner gave a dinner party for “Combat Command B” on August 18, 1944. Tea Brunner died at a young age, leaving behind five children. Her eldest son was Carlo Alberto Brunner.

Installation “Christian-Judeo Occident”. Photo: Dietmar Walser

The Jewish communities in Europe are in part significantly older than the Christian communities; after all, Europe’s Christianization was completed only in the Middle Ages. Nonetheless, until recently, the term “Christian Occident” was applied to Europe; hereby, eleven million Jews who had lived here prior to the National Socialist period were erased from European culture via linguistic usage. The relationship between Catholicism and Judaism was put on a more positive footing only under the impact of the Holocaust and with the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965). This had been preceded by the establishment of Christian-Jewish associations—as a critical reaction to the anti-Semitism and complicity of the churches in the genocide of the European Jews. It would take until 1986 until the first pope, John Paul II, Karol Wojtyła (1920-2005), would enter a Jewish house of prayer, namely, the Great Synagogue of Rome together with Chief Rabbi Elio Toaff.

< Pope John Paul II and Chief Rabbi Toaff on their way to the Great Synagogue of Rome in 1986, © Str/EPA/picturedesk.com

> Anti-Islam protests in the Czech Republic with Miloš Zeman on the occasion of the 26th anniversary of the “Velvet Revolution” in November 2015, © Matej Divizna, Getty Images

The catchword “Judeo-Christian West,” which has recently become popular, is a political battle cry. With its help, an old minority is meant to be coopted and mobilized against a new minority. It alludes to the cultural heritage of Greek and Roman antiquity as well as to the Bible. The fact that a significant part of this heritage is owed to Arabo-Islamic mediation is withheld as is the fact that Jews have always been forced into precarious life conditions and threatened by pogroms. Moreover, European protests against the construction of mosques recall prohibitions to build synagogues, which had been in force in large parts of Europe until well into the second half of the 19th century. Thus, the protests are also directed at the houses of worship of Muslims who speak Slavic languages and are shaping the culture of Southeastern Europe since hundreds of years. The concept of a European “Judeo-Christian community of shared values” blatantly contravenes Article 10 (1) of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union that declares: “Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion. This right includes freedom to change religion or belief and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or in private, to manifest religion or belief, in worship, teaching, practice and observance.”

Doron Rabinovici (Wien) über die Rede vom “christlich-jüdischen Abendland”:

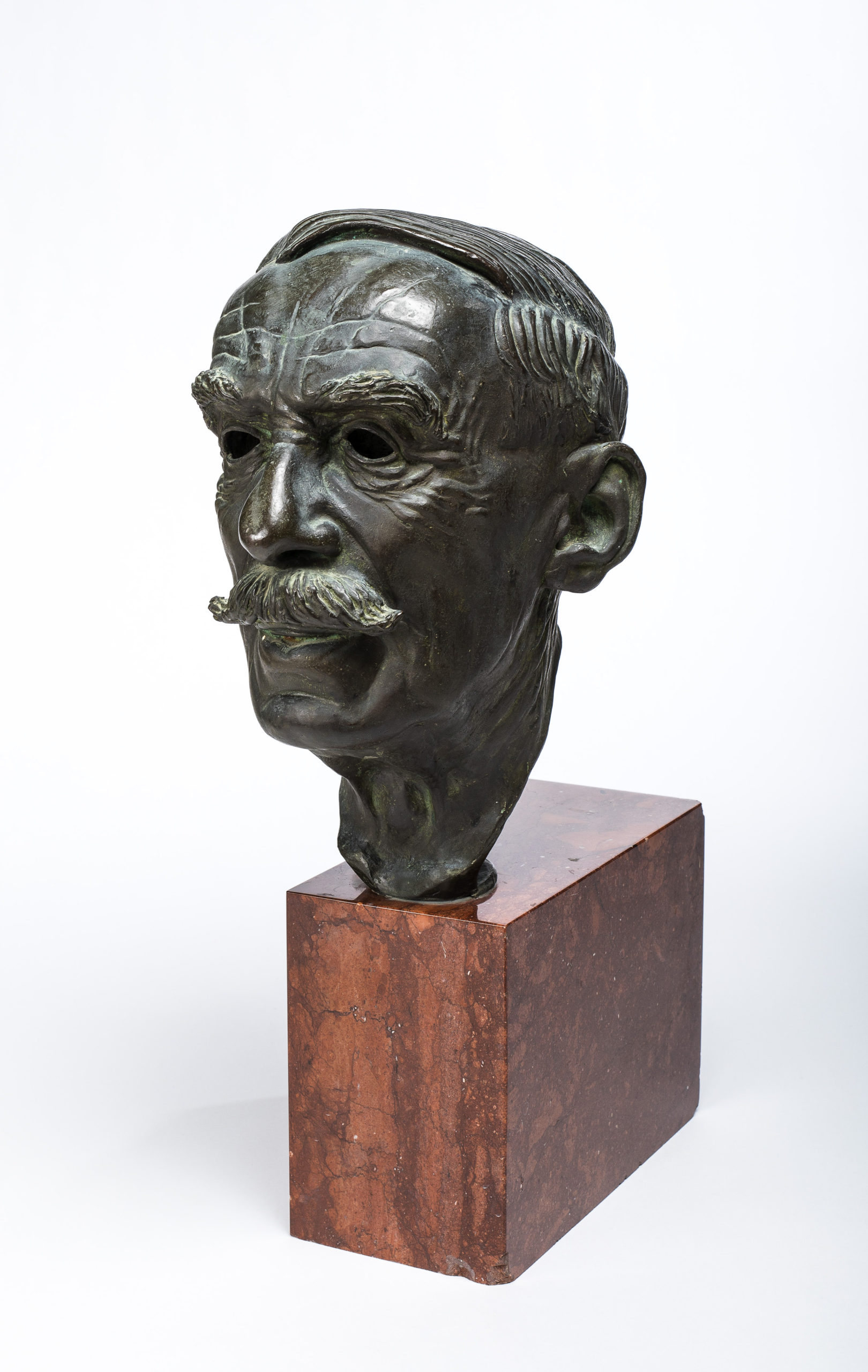

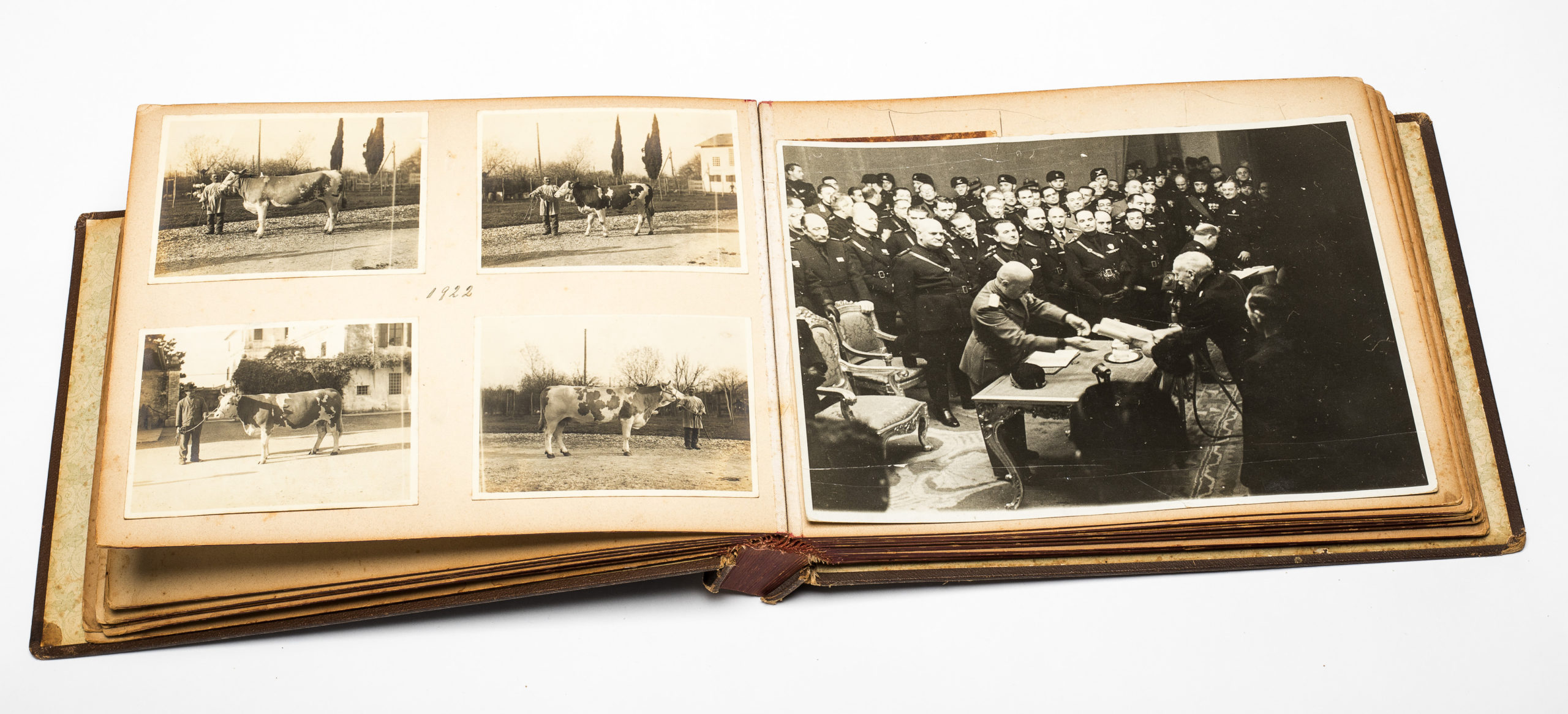

The second generation of the Hohenems immigrants in Trieste catapulted the Brunner family to their social and economic zenith. On the one hand, Rodolfo Brunner (1859-1956), eldest son of Carlo Brunner and Caroline, née Rosenthal, owned substantial shares of the family’s industrial enterprises (including chemicals, pharmaceuticals, mines, and shipping companies) and held management functions in companies such as Generali insurance, of which the Brunners were also shareholders. On the other hand, he specialized in the modernization and optimization of agriculture in Veneto and Friuli, not least in the Isonzo river delta. Politically, he was sympathetic to the Liberal-National Party of Trieste, which demanded a stronger orientation toward Italy, while he kept striving for reconciliation with Habsburg-Austrian interests. Like the majority of Trieste’s elite, but also many of the city’s Jews, he aligned himself with the Italian Fascists already early on. As business tycoon, he probably had frequent contact with the city’s top-ranking politicians. However, the reason for the meeting with Mussolini in this photograph is unknown; perhaps it is in connection with the award of the “Blue Star for Agricultural Merits,” which was bestowed on Rodolfo in 1937. His grandnephew Oscar Brunner (1900 – 1982) was an architect and sculptor, but only few of his works can be found in public collections.

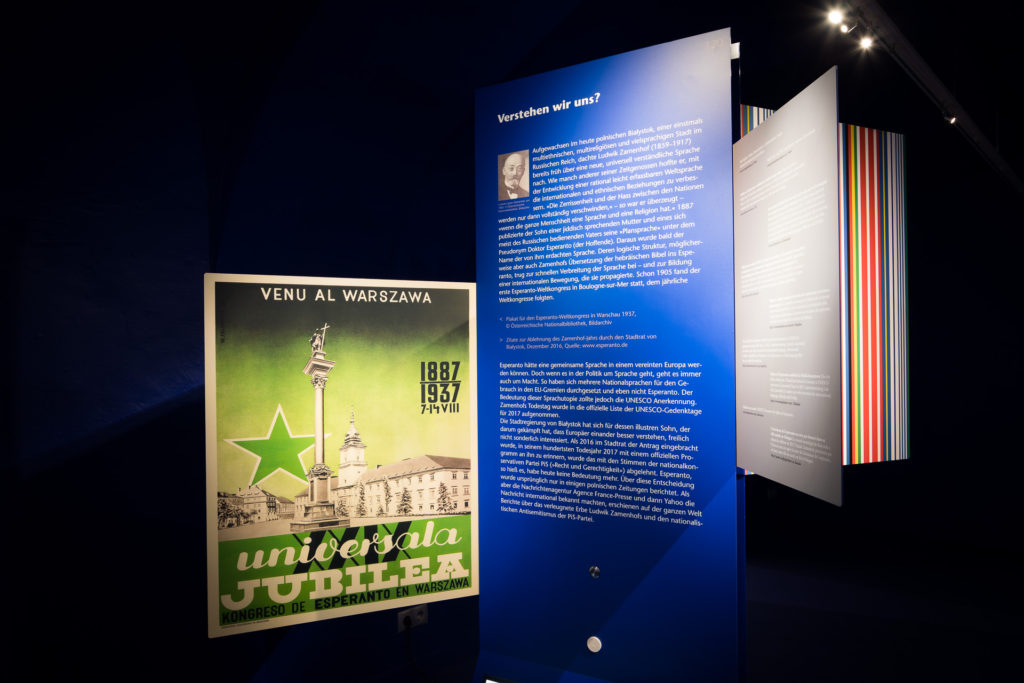

Installation Do We Understand Each Other? Photo: Dietmar Walser

Having grown up in Białystok, now Poland, a formerly multiethnic, multireligious, and polyglot city in the Russian Empire, Ludwik Zamenhof (1859–1917) began already early on to think about a new, universally understandable language. Like some of his contemporaries, he hoped to improve international and ethnic relations through the development of a easily graspable universal language. He was convinced that “division and hate among the nations will completely disappear only when all of humanity will have one language and one religion.” In 1887, the son of a Yiddish-speaking mother and a usually Russian-speaking father published his “planned language” under the pseudonym Doktoro Esperanto (the hopeful). This would soon become the name of the invented language. Its logical structure and possibly also Zamenhof’s translation of the Hebrew Bible into Esperanto contributed to the fast dissemination of the language—and to the formation of an international movement propagating it. Already in 1905, the first World Esperanto Congress took place in Boulogne-sur-Mer, which was followed by annual conventions around the world.

^ Ludwik Lejzer Zamenhof, ca. 1900, ©: Austrian National Library, Picture Archive

< Poster for the World Esperanto Congress in Warsaw 1937, © Austrian National Library, Picture Archive

> Quotes regarding the rejection of the Zamenhof-year by the Białystok municipal council, December 2016, © mounted by Günter Kassegger, source: www.esperanto.de

Esperanto had the potential of becoming a common language in a united Europe. Yet, politics and language is always also a matter of power. Hence, several national languages have prevailed for use in EU bodies and not Esperanto. However, UNESCO has paid tribute to the significance of this linguistic utopia. Zamenhof’s death anniversary was included in the official list of UNESCO commemoration days for 2017. Then again, the Białystok municipal government failed to display any particular interest in the city’s illustrious son who had worked to enable Europeans to better understand each other. When in 2016, a motion was made in the municipal council to commemorate him with an official program on the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of his passing in 2017, it was rejected with the votes of the national-conservative PiS (“Law and Justice”) party. Esperanto, it was argued, had no longer any significance today. This decision was originally reported only in several Polish newspapers. However, when this was brought to international attention by the newsagency Agence France-Presse and then by Yahoo, reports about Ludwik Zamenhof’s repudiated heritage and the PiS party’s nationalist anti-Semitism were published all over the world.

Liliana Feierstein (Berlin): About Esperanto as a Jewish, European, and International language

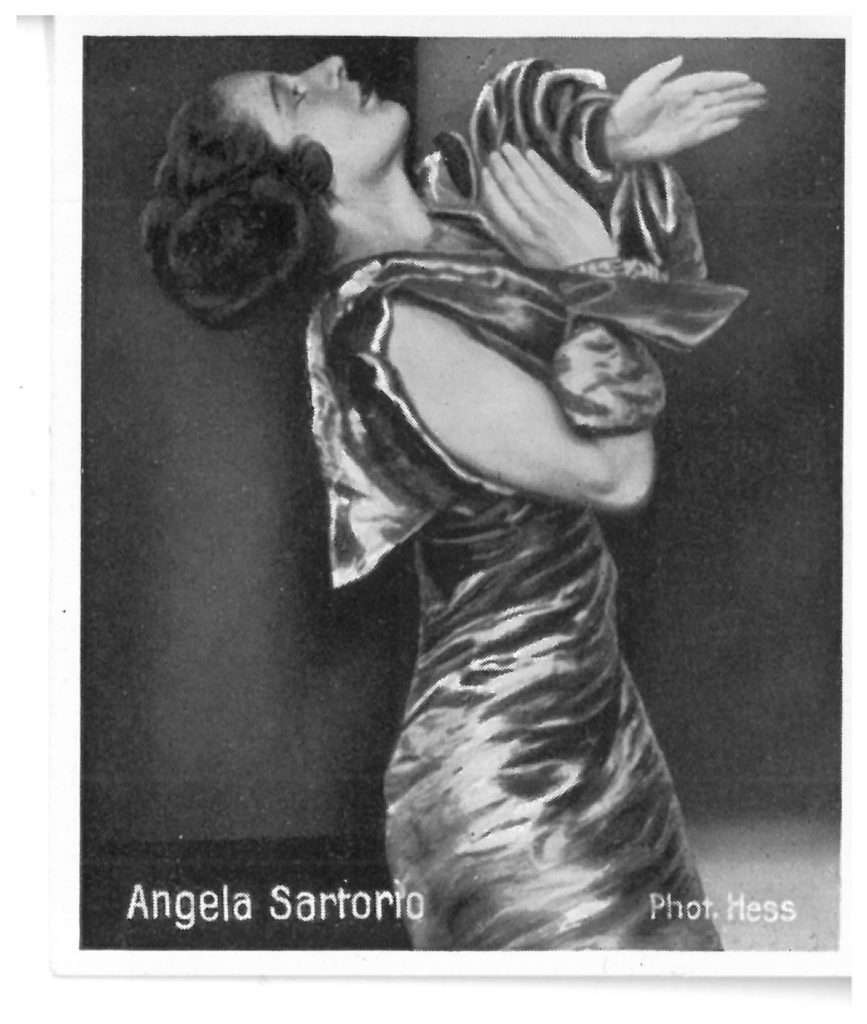

Angiola Elise Sartorio (1903-1995) was the daughter of Julie Bonn and the Italian painter Giulio Aristide Sartorio. Her grandmother Elise Bonn, née Brunner, a sister of the “Triestine brothers” of the first generation, had married into the Frankfurt banking family Bonn. Following her parents’ separation and years spent in England and Sweden, Angiola Sartorio moved back to Germany where she became acquainted with the ideas of modern dance and entered the company of Kurt Jooss, a student of the influential dance theoretician Rudolf von Laban, to eventually embark on a remarkable career as choreographer and dancer. In 1933, she created a choreography for Max Reinhardt’s Italian stage production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in Florence. She rejected, however, Reinhardt’s invitation to accompany him to the USA. She had just opened a dance school of her own in Florence where numerous dancers fleeing from Germany and Austria had found work starting in 1933. In 1939, Angiola Sartorio decided to flee to the USA herself, first to New York, then to Santa Barbara where she continued teaching dance and choreography. She remained professionally active until the end of her life and took a stand for minorities and civil rights.

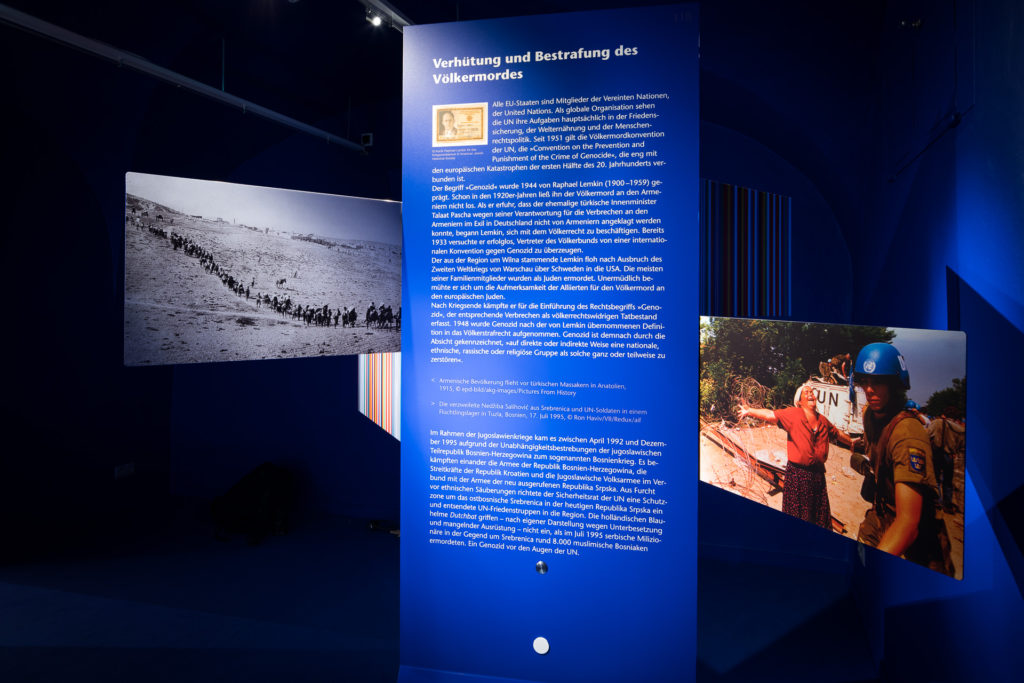

Installation Prevention and Punishment of Genocide. Photo: Dietmar Walser

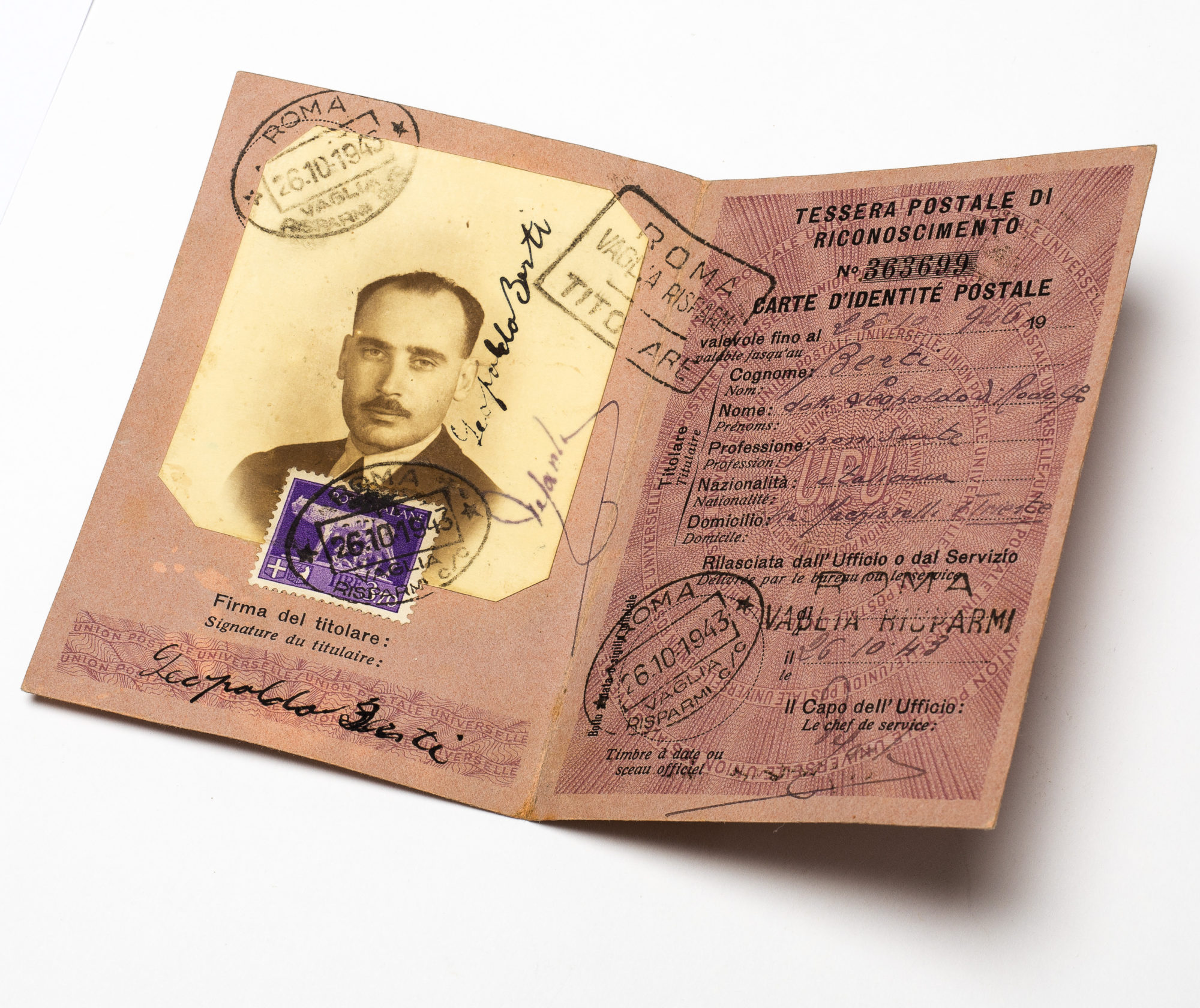

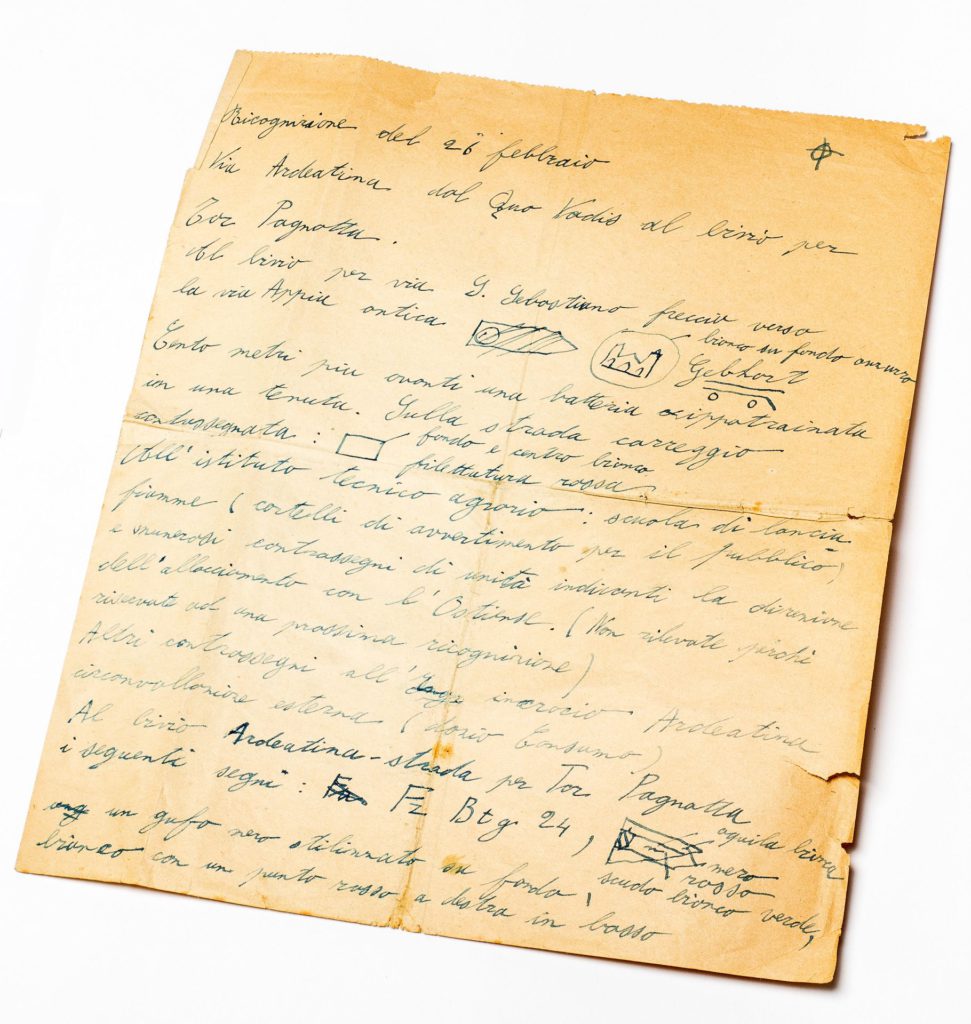

All EU states are members of the United Nations. As a global organization, the UN sees its tasks mainly in maintaining peace, achieving worldwide food security, and protecting human rights. Since 1951, the UN’s “Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide” is in force; it is closely linked to the European catastrophes of the first half of the 20th century. The term “genocide” was coined in 1944 by Raphael Lemkin (1900-1959). As early as in the 1920s, he was gripped by the genocide of the Armenians. When he learned that the Armenians could not prosecute the responsible for the crimes against the Armenian people Talaat Pasha, the former Turkish minister of the interior, in his exile in Germany, Lemkin began to immerse himself into international law. Already in 1933, he tried without success to persuade representatives of the League of Nations of the need for an international convention against genocide. Lemkin, who came from the region of Vilna, escaped at the outbreak of World War II from Warsaw via Sweden to the USA. As Jews, most of his family members were murdered. Unflaggingly, he sought to direct the Allies’ attention to the genocide of the European Jews. After the end of the war, he fought for the adoption of the legal term “genocide,” which conceives relevant crimes as an act of violation against international law. In 1948, genocide as defined by Lemkin was incorporated into international criminal law. Accordingly, genocide means “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.” ^ ID card of Raphael Lemkin for the Ministry of War, © American Jewish Historical Society < Armenians fleeing from Turkish massacres in Anatolia, 1915, © epd-bild/akg-images/Pictures From History > Distressed Nedžiba Salihović from Srebrenica and UN soldiers in a refugee camp in Tuzla, Bosnia, July 17, 1995, © Ron Haviv/VII/Redux/aif In the course of the Yugoslav Wars, the so-called Bosnian War, sparked by the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s drive for independence, took place between April 1992 and December 1995. Fighting against each other were the army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the armed forces of the Republic of Croatia, and the Yugoslav People’s Army together with the army of the newly proclaimed Republika Srpska. Fearing ethnical cleansing, the UN Security Council established a safe area around the eastern Bosnian town of Srebrenica in today’s Republika Srpska and dispatched UN peacekeeping troops to the region. The Dutch blue helmets Dutchbat failed to intervene—by their own admission because of understaffing and a lack of equipment—when in July 1995 Serbian militiamen murdered around 8,000 Muslim Bosniaks. A genocide before the eyes of the UN.

Installation Europe Boundless. Photo: Dietmar Walser

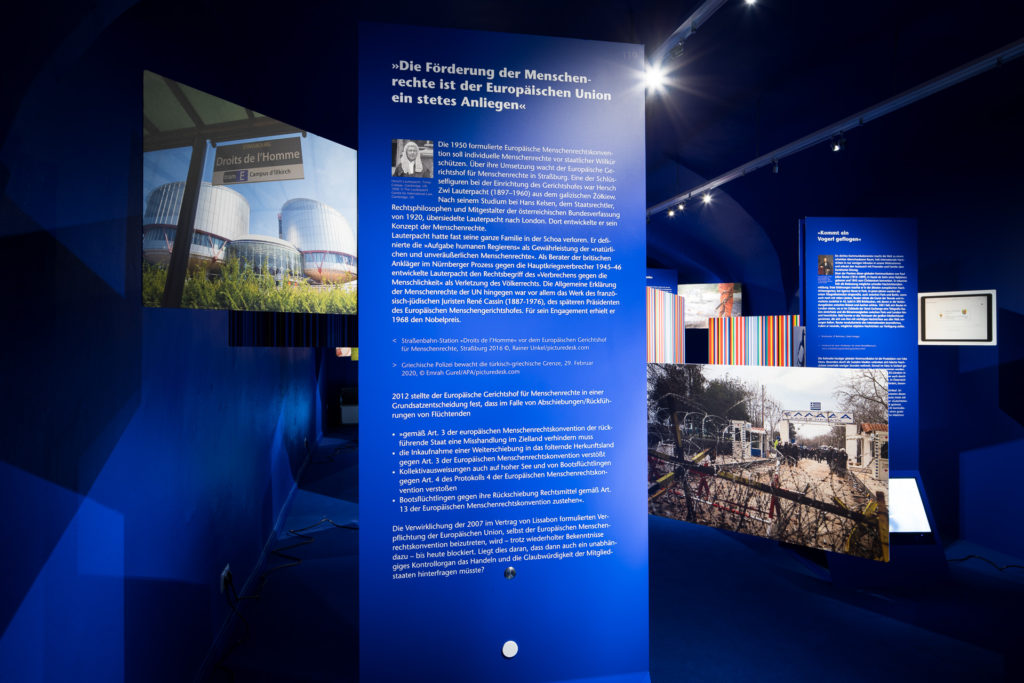

Installation Promotion and Protection of Human rights. Foto: Dietmar Walser

The European Human Rights Convention formulated in 1950 aims to safeguard the protection of individual human rights against state arbitrariness. The European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg watches over its implementation. One of the pivotal figures in the establishment of the European Court of Human Rights was Hersch Zvi Lauterpacht (1897–1960) from Żółkiew in at the time Austro-Hungarian Galicia. After his studies in Vienna under Hans Kelsen, the expert in constitutional law, legal philosopher, and co-creator of the 1920 Constitution of Austria, Lauterpacht moved to London. Here he developed his concept of human rights. Possibly, its humanitarian character is linked to his personal experience: Lauterpacht had lost almost his entire family in the Shoah. He defined the “issue of human government” as securing the “natural and inalienable rights of man.” As adviser to the British prosecutors at the Nuremberg trials against the major criminals of war in1945-46, Lauterpacht developed the legal concept of “crimes against humanity” as elements of offense against international law. ^ Hersch Lauterpacht, Trinity College, Cambridge, UK, 1958, © The Lauterpacht Centre for International Law, Cambridge, UK < Tramway station “Droits de l’Homme” in front of the European Court of Human Rights, Strasbourg 2016 ©, Rainer Unkel/picturedesk.com > Greek police guarding the Turkish-Greek border, February 29, 2020, © Emrah Gurel/APA/picturedesk.com In 2012, the European Court of Human Rights decided in a landmark judgement that in case of expulsion/refoulement of refugees

Implementation of the European Union’s commitment as formulated in the 2007 Treaty of Lisbon to accede to the Human Rights Convention has been blocked to this day—repeated avowals to do so notwithstanding. Could it be that then also an independent monitoring body would have to scrutinize the actions and credibility of the member states?