by Felicitas Heimann-Jelinek

European Diary, 24.6.2021: In August 1941, the year of the systematic establishment of the Nazi extermination camps, Winston Churchill reacted disturbed in the face of the beginning mass murder of the European Jews with the words: “We are in the presence of a crime without a name.” The man who was to give the crime a name and ensure its future punishment by the International Criminal Court was born 121 years ago on this day in a village in Belarus, near Wilna: Raphael Lemkin.

Lemkin was awarded a doctorate in law from the University of Lemberg (today Lviv). His choice of studies was prompted by the self-imposed question of why the Turkish massacre of a million Armenian women, children and men was not considered a crime, but the killing of a single person was very much a crime under universal law.

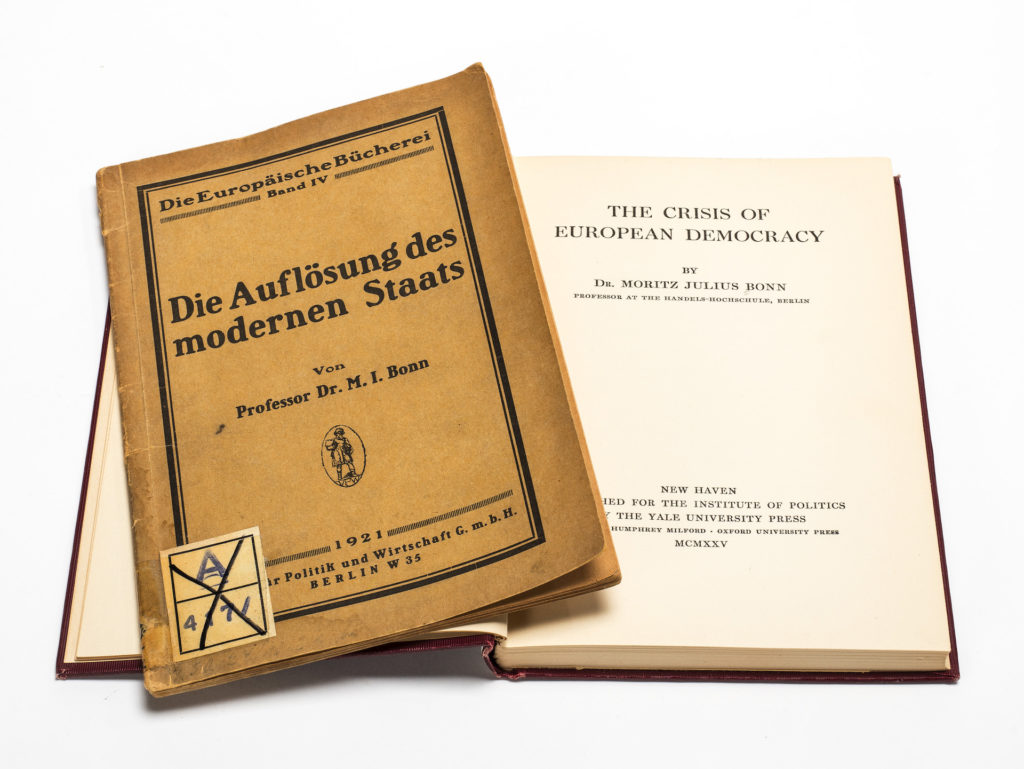

In January 1933, Hitler was appointed Chancellor of the German Reich, the Weimar Republic was crushed, and a centralist dictatorship was introduced. Opponents were interned in specially established camps as early as March. By this time, Lemkin was already a respected lawyer in Warsaw, well-versed in international law and well-connected. And he suspected that this was only the prelude to something much worse.

Lemkin drafted a proposal that would define the extermination of national, “racial,” and religious groups internationally as a crime, and sent it to an international conference. But it found little support, even as anti-Semitism became Germany’s national policy. The fascist frenzy that had gripped much of the world left many blind and deaf. When Hitler invaded Poland in 1939, Lemkin knew his premonitions would be fulfilled.

He fled Warsaw, made his way to his parents, only to say goodbye to them forever. Together with 38 other family members, they were murdered as Jews by the Nazis. He himself managed to escape to the United States, where a friend got him a job at Duke Law School in North Carolina.

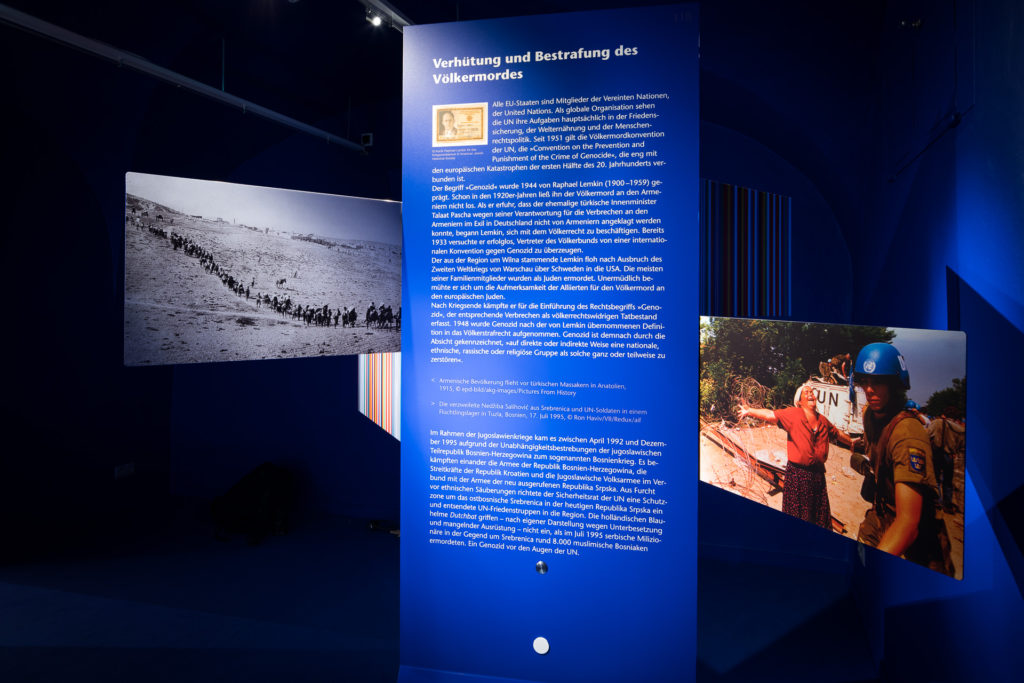

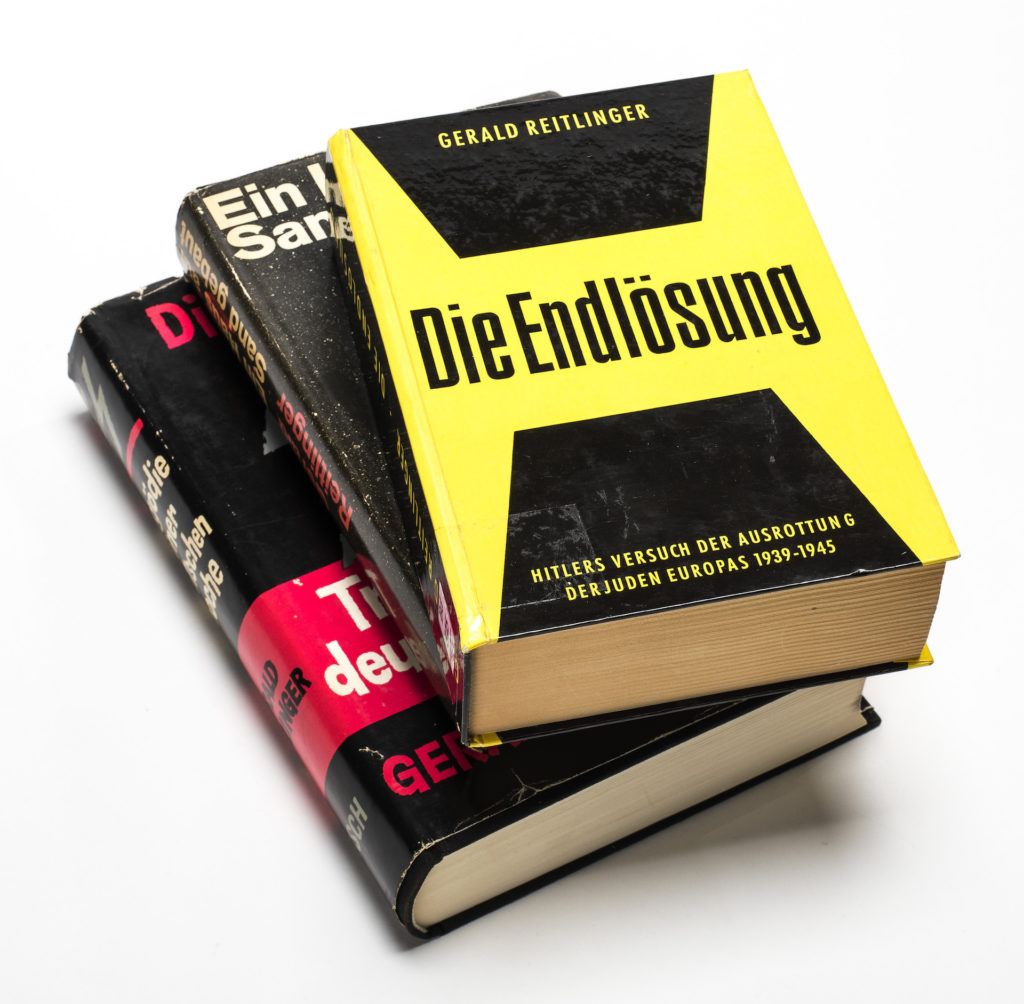

Raphael Lemkin searched feverishly for a term that would do justice to the crime that took place before the eyes of the world. The term mass murder, he argued, was not adequate for the murder of European Jews because it did not incorporate the national, ethnic, or religious motivation of the crime. Nor, he argued, did denationalization capture the crime, since it was aimed at cultural, but not necessarily biological, extermination. His reflections eventually led him to a neologism: genocide. The word is composed of the ancient Greek genos (clan, race, offspring, gender) and the Latin caedere (to kill), the German translation being genocide. However, the conceptualization was only the prerequisite for the actual goal. Lemkin did everything he could to ensure that genocide would be treated and condemned as an internationally justiciable crime.

Lemkin was bitterly disappointed by the Nuremberg trials, in which little happened to codify genocide as an international crime – and nothing to prevent it in the future. But he did not give up, corresponding, lobbying, drafting, and revising the text for a genocide convention. And indeed, after a tireless struggle, he was successful. On December 9, 1948, the United Nations Organization adopted his proposal for a genocide convention. A short time later, Lemkin fell so seriously ill that he had to be hospitalized. Doctors did have trouble finding the cause. He happily diagnosed himself with “genociditis. Exhaustion from working on the Genocide Convention.”

The man who gave a name to the greatest crime of the 20th century and precisely defined the crime of genocide under international law died poor and alone in a one-room apartment in New York in 1959.