Installation Prevention and Punishment of Genocide. Photo: Dietmar Walser

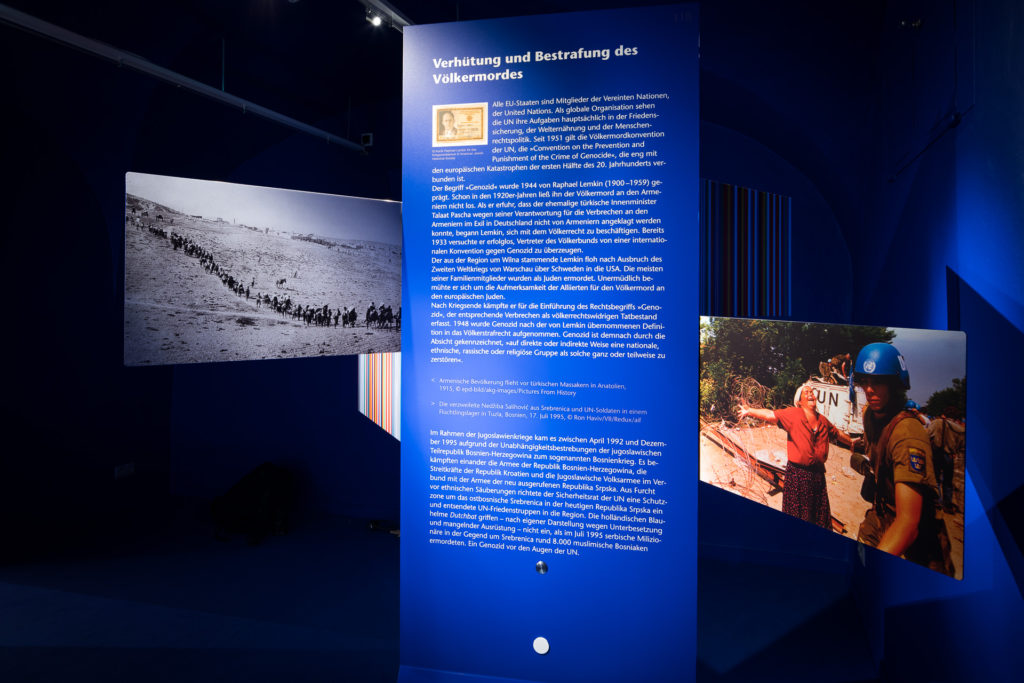

All EU states are members of the United Nations. As a global organization, the UN sees its tasks mainly in maintaining peace, achieving worldwide food security, and protecting human rights. Since 1951, the UN’s “Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide” is in force; it is closely linked to the European catastrophes of the first half of the 20th century. The term “genocide” was coined in 1944 by Raphael Lemkin (1900-1959). As early as in the 1920s, he was gripped by the genocide of the Armenians. When he learned that the Armenians could not prosecute the responsible for the crimes against the Armenian people Talaat Pasha, the former Turkish minister of the interior, in his exile in Germany, Lemkin began to immerse himself into international law. Already in 1933, he tried without success to persuade representatives of the League of Nations of the need for an international convention against genocide. Lemkin, who came from the region of Vilna, escaped at the outbreak of World War II from Warsaw via Sweden to the USA. As Jews, most of his family members were murdered. Unflaggingly, he sought to direct the Allies’ attention to the genocide of the European Jews. After the end of the war, he fought for the adoption of the legal term “genocide,” which conceives relevant crimes as an act of violation against international law. In 1948, genocide as defined by Lemkin was incorporated into international criminal law. Accordingly, genocide means “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.” ^ ID card of Raphael Lemkin for the Ministry of War, © American Jewish Historical Society < Armenians fleeing from Turkish massacres in Anatolia, 1915, © epd-bild/akg-images/Pictures From History > Distressed Nedžiba Salihović from Srebrenica and UN soldiers in a refugee camp in Tuzla, Bosnia, July 17, 1995, © Ron Haviv/VII/Redux/aif In the course of the Yugoslav Wars, the so-called Bosnian War, sparked by the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s drive for independence, took place between April 1992 and December 1995. Fighting against each other were the army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the armed forces of the Republic of Croatia, and the Yugoslav People’s Army together with the army of the newly proclaimed Republika Srpska. Fearing ethnical cleansing, the UN Security Council established a safe area around the eastern Bosnian town of Srebrenica in today’s Republika Srpska and dispatched UN peacekeeping troops to the region. The Dutch blue helmets Dutchbat failed to intervene—by their own admission because of understaffing and a lack of equipment—when in July 1995 Serbian militiamen murdered around 8,000 Muslim Bosniaks. A genocide before the eyes of the UN.